“Big iron” instruments, aka diagnostic radiology equipment such as x-ray, ultrasound, and CT scanners, are indispensable for diagnosing and guiding treatment for an array of conditions from tumors to arthritis to fractures. While a tremendous asset for hospitals, these instruments are traditionally large, heavy, power hungry, and expensive. They are also difficult to acquire, install, and use.

As demand for the tests and therapies these instruments enable continues to rise, service providers need equipment that is more affordable, more compact, and more power efficient — i.e., less big iron and more digital age.

Future generations of scanners, for example, need to deliver high-power imaging capabilities within a smaller footprint. This can make them easier to install as well as more comfortable for both patients and operators when in use.

Powering MRI Coils

The squeeze to miniaturize is present throughout the entire system, including the design of power supplies. However, the power requirements of some subsystems can conflict with this. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners, for example, the intense constant magnetic field that aligns the body’s molecules for scanning may be provided using cryogenically cooled permanent magnets or superconducting coils, with coils most commonly preferred in today’s high-end systems. And for this application (obviously depending on the size and type of scanner) the peak power demand can exceed 20 kW.

To achieve the desired field strength, which can be between 1.5 and 7 Tesla (T) depending on the system type and target uses, the coils are driven with current up to 500 A. Few manufacturers produce power semiconductors that could handle such high current in a single switch design. And, while two or more devices could be connected in parallel, it should be noted that current sharing can be difficult to manage.

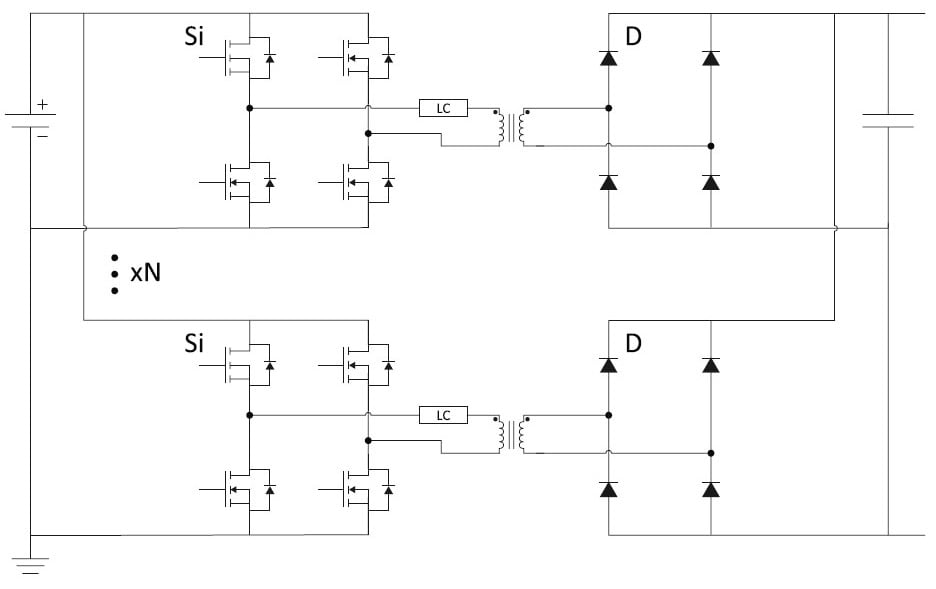

Also, MOSFETs with high current rating tend to have high on resistance, RDS(on), which results in relatively large energy losses that impair efficiency. Moreover, the output voltage must be extremely stable, and this requires either a large, bulky and usually expensive capacitor or a switching frequency that is impractically high for silicon devices. Instead, a multi-phase interleaved topology is typically used that comprises multiple phase-shifted outputs (see Figure 1).

Interleaving the power supply phases shares the total output current between several MOSFETs, alleviating the requirements for devices with a high maximum current rating. In addition, interleaving results in a high-ripple frequency that can be filtered using smaller capacitors. While this approach enables designers to ensure satisfactory power for the MRI superconducting coils, the resulting circuitry is complex and involves a large bill of materials.

Silicon carbide power MOSFETs now offer an alternative. The devices are known to operate efficiently at high switching frequencies and the RDS(on) is also lower in relation to the maximum voltage and current ratings. With continued development in fabrication processes, realizing improvements in substrate quality, wafering, and epitaxy, the resulting rise in yield is changing the economics of silicon carbide (SiC).

In addition to these gains, new SiC MOSFETs using third-generation technology recently announced by SemiQ also benefit from significantly reduced die size that further increases the number of dies produced per wafer; an extra factor increasing the affordability of SiC in applications that have been considered too cost sensitive for SiC until now. A compact and cost-effective alternative can now be achieved.

Silicon IGBT or SiC MOSFET

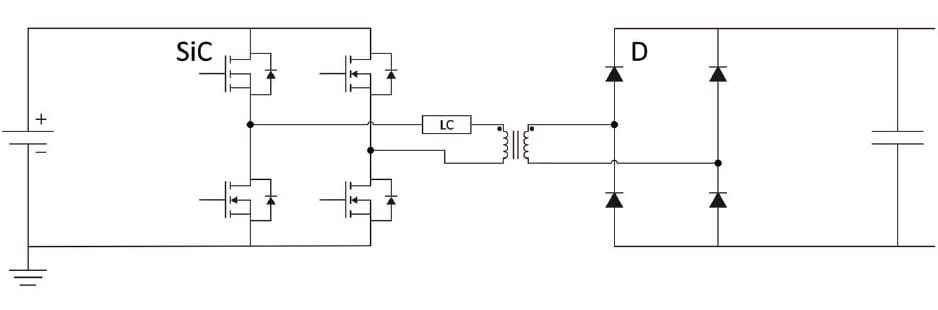

The latest SiC MOSFETs enable designers of big iron medical equipment to create simpler power supplies and avoid complex current-sharing or multi-phase designs. Figure 2 shows a simplified output circuit that can replace the interleaved circuit of Figure 1.

IGBTs operate at up to 20 kHz as a practicable maximum, and replacing these with SiC-based devices to deliver switching frequencies of 100 kHz (and higher) delivers power efficiency gains and simplified thermal management. High switching frequencies allow designers to replace large capacitors or capacitor arrays with fewer, smaller and lower-cost devices for filtering, while at the same time achieving very high efficiency to allow more compact and lightweight designs.

In similar applications, smaller, more responsive power supplies that are built with SiC devices and operate at high frequencies, enable devices like linear accelerators (LINACs) in radiation therapy equipment to ensure consistent treatment dosages. Also, in laser surgery systems, the increased power output and higher efficiency of SiC-based PSUs can ensure greater accuracy and safety in surgical lasers.

In lower-powered big iron medical equipment, instruments such as skin treatment lasers can operate at power ratings up to about 1 kW. In this power range, adopting SiC MOSFETs enables higher switching frequencies that permit smaller capacitors to drive the emergence of smaller, lower-cost systems that can be moved more easily between treatment rooms and even installed in mobile clinics to improve the services available to rural and remote communities. Compared with traditional bulky power systems, a more compact design using SiC devices can provide a sub-kilowatt power supply for a skin treatment laser. For example, SemiQ engineers have supported successful development projects that have achieved a 75 percent reduction in the size of the power stack for skin treatment systems, compared to existing power supplies containing silicon IGBTs.

It is now both technically possible and cost effective to raise the power capability of an existing power supply by a factor of approximately four, within the same footprint as an existing design based on silicon technology. Smaller size and reduced heat dissipation can not only enable historically large and bulky equipment to become easier to use but also offers the prospect of portable equipment that could allow small mobile health services to offer access to imaging and radiotherapy treatments previously only possible in hospitals or large and expensive mobile trucks.

Conversely, while miniaturization is a key advantage to be gained by adopting SiC in new designs, it is also possible to increase power output within a comparable footprint, such as where the form factor may be constrained by industry standards or physical limitations of the equipment. Leveraging the greater power density made possible by raising the operating frequency can deliver an approximately threefold increase in the PSU power rating, as well as delivering a boost in efficiency. Thus, low-power equipment operating in the 2-3 kW range can be upgraded to deliver the performance of high-end equipment operating at power levels up to 10 kW.

Generational Improvements in SiC

SiC MOSFETs can operate efficiently at much higher switching speeds than silicon devices and can withstand high applied voltages as well as high operating temperatures. This lets designers simplify power circuits, replacing complex interleaving and current sharing arrangements, or large and bulky power stacks, with circuits comprising fewer power switches and smaller capacitors. In addition, fewer power MOSFETs need to be connected in parallel to achieve the target power output. Thus, SiC technology enables simplified topologies with hard switching while also enabling higher power ratings.

As SiC power MOSFETs become smaller, more efficient and more cost-effective with each successive generation, the benefits of advanced wide-bandgap power semiconductors will improve further, enabling their use in an increasing variety both high performance and cost-sensitive applications.

This article was written by Jianfu Fu, SiC Module Application and Field Application Engineer, SemiQ, Lake Forest, CA. For more information, visit here .