The rapid pace of innovation in the medical device industry puts ever increasing pressure on manufacturers to achieve greater geometrical precision, increase device lifetime and reliability, and simultaneously reduce the cost of making diverse portfolios of products. A key step in manufacturing medical implants, such as cardiovascular stents, is laser micro machining, where the basic device geometry is cut from an extruded tube or other raw substrate. Today, most device production is performed using continuous wave (CW) lasers, which have been commercially available for decades. Nonetheless, manufacturers are switching to ultra-short pulse (USP) lasers for new device production lines at a rapid rate. In this article, we describe why this is happening and what basics device and process engineers should know to be successful with USP laser machining.

USP Laser Micro Machining Fundamentals

Medical device manufacturers typically want to immediately answer two essential questions when evaluating a new machining technology:

- Will it achieve the necessary quality for the device specification?

- Is the process fast enough for the required production run rate?

These questions are usually answered through several iterations of laser application demonstration by the medical device manufacturer and laser supplier. The closer the collaboration, the more accurate the answers.

USP laser micro machining is selected by manufacturers when they want to avoid a heat affected zone (HAZ)—the collateral damage left by machining with conventional lasers. More on this topic in the next section. Simply put, CW lasers remove material by melting it, and USP lasers remove material by vaporization. The options for industrial USP lasers today include pulse durations from tens of picoseconds (ps) down to a few hundred femtoseconds (fs). There are three ranges with the greatest number of supplier options:

- Standard pico lasers: 5 to 10 ps

- Long femto lasers: 700 to 900 fs

- Short femto lasers: 300 to 500 fs

The optimal pulse duration for a given manufacturing challenge depends upon multiple factors, including the required post-machining quality. Beyond prevention of HAZ, kerf taper and sidewall average roughness are common figures of merit.

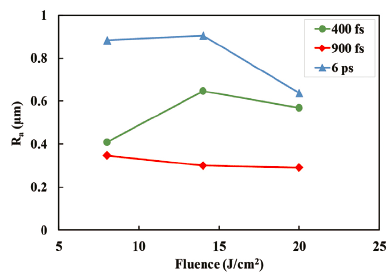

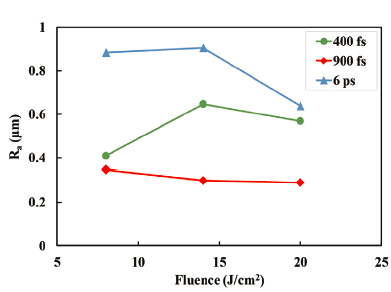

The average roughness (Ra) for the sidewall surface also shows a strong dependence on pulse duration. As an example, we measured average roughness versus pulse duration for cutting Durnico, a maraging steel, at several fluences. The data, as shown in Figure 1, reveals that 900 fs pulse duration consistently produces lower roughness than either 6 ps or 400 fs. This phenomenon is not rigorously studied at this point, and the pulse duration dependence may vary with other metals or experimental conditions.

Along with machined-part quality, machining rate is a critical factor in determining the best laser source for a manufacturing process. Of course, generally more power means faster material removal, to a point. When trying to avoid any HAZ, the net heat deposit in the finite volume comprising the part will limit actual power used on the target. Even short femto lasers deposit a certain amount of heat with each pulse. This tiny amount of heat will accumulate over many pulses to result in HAZ if the process is not optimized. Nonetheless, for a given power range, the machining rate can be increased before seeing HAZ by selecting the best pulse duration.

The information presented here was gathered using typical conditions for micro machining with USP lasers, e.g., 150 mm focal length lens, nitrogen purge gas, and several hundred kilohertz pulse repetition rate. A manufacturer’s results will directly depend on material type and thickness, focusing conditions, purge gas type and pressure, and tool path. These factors will be described in greater detail in the last section of this article. First, we will examine practical benefits to medical device manufacturing by using USP lasers.

Precision Stent Machining

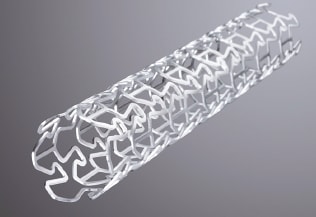

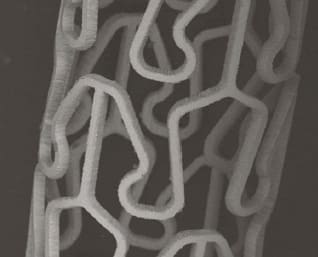

One of the first commercial success stories for USP lasers in precision manufacturing is machining of cardiovascular stents. Manufacturing these devices requires extraordinary precision to achieve micron level geometrical tolerances and avoid defects, like stress risers from heat build-up during machining. Since metal stents are usually intended as permanent implants in the body, defects can have catastrophic consequences. Moreover, as new designs for smaller stents emerge, e.g., for cranial and peripheral stents, the challenges imposed on the manufacturing process grow ever greater.

When micro machining metals with conventional lasers, there can be several deleterious side effects, including recast of molten material, prominent burr along the kerf, and HAZ. Even when recast and burr can be minimized, conventional lasers always leave HAZ that is a few microns to tens of microns wide adjacent to the machining area. This can be easily discerned as a region of modified crystal structure when the part is examined under high magnification. One or more post-processing steps must remove each side effect before the final device is polished and assembled.

Bead blasting and manual honing are common post-processing steps to remove recast. Chemical etching, also called acid pickling, is typically necessary to remove HAZ and burrs. Although these have worked effectively for previous generations of stents, they impose both additional expenses and limitations in the end-to-end manufacturing process. For example, manual honing results will vary depending on the technician performing the operation, and the expense of manual labor is often dominant in per-part costs. Chemical etching rates depend upon localized material quality and shape, and the handling of the caustic chemicals represents consumables expense and safety requirements for the manufacturing site.

Another important factor is the more universal efficacy of USP lasers for machining different materials and stent patterns. Figures 3 and 4 show a stent cut from an extruded tube of Nitinol (NiTi) using a USP laser. NiTi, and other common metals used for implants, such as chromium cobalt, stainless steel, and titanium, have sufficiently similar laser-material interaction properties to make them accessible to a single USP laser source. USP laser machining employs photo-ionization as the initial activation mechanism, as opposed to linear absorption in the case of CW lasers. Material removal with USP lasers is more wavelength-independent and utilizes a narrower range of power and pulse energy parameters for optimal results. In practice, this means a single laser workstation can be used for producing a variety of medical devices. (See Figures 3 and 4)

In the case of stents, USP lasers enable machining of smaller diameters, narrower struts, and more complex flexure patterns. The lower limit on stent diameter has traditionally been imposed by back-wall damage using conventional lasers. Owing to the finite threshold for photoionization, this can be avoided for diameters

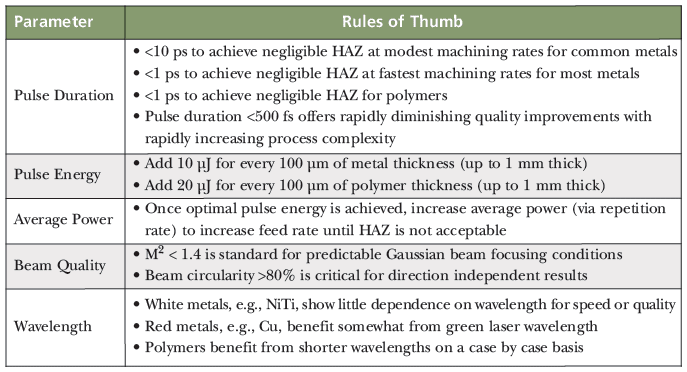

How to Achieve the Best Results

Even though USP lasers are becoming more common in manufacturing settings, it must be understood that using USP requires specialized knowhow. That is, a manufacturer cannot simply drop in a USP laser where a CW laser was used before and expect great results. The implication here is that manufacturers must work with an expert in USP laser machining and bring enough knowledge in-house to optimize the process in full production. Table 1 offers a summary of some of the better understood rules of thumb for selecting laser parameters. These must be combined with other process parameters—like beam polarization and focusing conditions, part or beam motion, process gas type and pressure, and debris management—to achieve the desired outcome in manufacturing.

The average power guideline is more straight-forward. The process should use sufficient pulse energy to cut through the material, usually in a single pass, and then the pulse repetition rate should be increased to advance the feed rate. With the high power industrial USP lasers available today, limitations on average power usually stem from the part size and motion control system. Since even the shortest pulses deposit a finite amount of their energy as heat, a large enough number of pulses delivered to a very small part will create HAZ. The part or the beam can be moved around faster, to an extent, but then the part size becomes the constraining factor. In practice, manufacturers will sometimes tolerate a certain amount of HAZ in order to hit a desired part processing time.

Laser suppliers typically specify laser beam quality as the M-squared parameter (M2), or how closely their product matches an ideal Gaussian beam (M2 = 1). Laser sources with M2 < 1.4 seem to be accepted by most of the industry as sufficient for precision micro machining. Nonetheless, beware of lasers with elliptical beams, astigmatism or other distortions that are not necessarily revealed by the M2 figure. These beam defects lead to direction-dependent kerf width and other problems. A good way to test a laser source is by measuring ablation spots through focus of a known lens.

The laser’s wavelength does not currently play a large role when users select the right laser for manufacturing metal stents and other medical devices. As mentioned above, the common metals used for stents and other implants are white metals (those that are silvery in hue). For devices that use red metals (i.e., gold or copper), wavelength may play a more significant role. In addition, polymer machining has much greater dependence on laser wavelength owing to the higher photon energy and the role of multi-photon ionization in polymer ablation. Polymers are also more heat sensitive than metals, and wavelength strongly impacts residual linear absorption of laser energy that creates heat. As device features become smaller in future designs, the laser’s wavelength may become more important for reducing spot size on the part.

Here we mentioned polymer machining for the first time, and indeed, the industry’s knowledge about USP machining of polymers is much less mature. Though we include some guidance on polymer machining in Table 1, these are early learnings and are the subject of considerable debate in the technical community. On the other hand, there is potentially even greater value offered by USP processing of polymers, given their heat sensitivity and difficulty in precision micro machining. We expect rapid development in this area in the next few years.

The competitive landscape for medical devices is evolving rapidly, forcing manufacturers to adapt to new demands for precision and determinism. USP lasers—with pulse duration in the range of hundreds of femtoseconds to tens of picoseconds—have emerged as critical tools to make next generation medical devices more reliably and cost-effectively. Along with the new tools, however, manufacturers must develop a deeper understanding of USP laser machining.

This article was written by Michael Mielke, TruMicro Program Manager, TRUMPF, Inc., Farmington CT. For more information, Click Here . MD&M West, Booth 3254