Bruno Boutantin,

Extrude Hone

Knee replacement implants must balance strength, wear resistance, and precision geometry to restore mobility and reduce pain for millions of patients worldwide. Yet one of the most challenging regions of the knee femoral component to manufacture is the intercondylar area — the central box that accommodates the cam mechanism. Traditionally produced using CNC milling, this section involves complex geometry, demanding tolerances, and hard-to-machine materials like cobalt-chromium (CoCr).

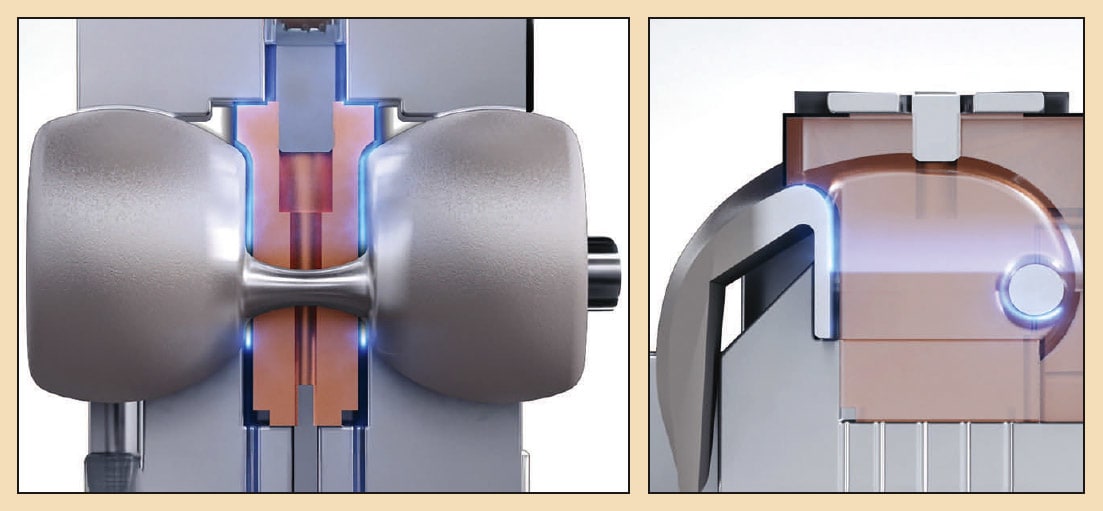

In March 2025, Extrude Hone introduced an alternative approach: electrochemical machining (ECM). By applying this process to the knee implant intercondylar area, manufacturers can achieve superior surface finish, tighter tolerances, and dramatic reductions in machining time and cost compared to CNC.

Why Reconsider CNC for Knee Implant Manufacturing?

The knee implant’s intercondylar region poses unique manufacturing challenges. The area must be precisely shaped to ensure smooth articulation between the cam and box, yet it is located between bearing surfaces that cannot be compromised. CNC milling has long been the default solution, but it comes with drawbacks:

Machining stress and heat can affect material properties.

Long cycle times — up to 17 minutes per piece on average.

Higher costs driven by tool wear, multiple finishing passes, and labor.

Limitations with hard alloys such as CoCr, which significantly increase machining difficulty.

ECM avoids many of these limitations.

The ECM Advantage

Electrochemical machining is a cold, stress-free process that uses electrical current and electrolyte chemistry to dissolve material at precisely targeted locations. Instead of cutting with force and heat, ECM removes material without mechanical contact, enabling highly repeatable and precise outcomes. Key advantages include:

Stress-Free Processing: No mechanical forces, no heat-affected zones, and no risk of microcracks.

Tight Tolerances: Dimensional control within ±0.1 mm (0.004 in.) and parallelism within ±0.05 mm (0.002 in.).

Superior Surface Finish: Roughness improved below Ra 0.2 μm (8 Ra μin.), reducing the need for polishing.

One-Pass Efficiency: Roughing and finishing can be achieved in a single pass, reducing process steps.

Material Versatility: ECM handles difficult alloys like CoCr with the same ease as stainless steel.

For orthopedic manufacturers, this means consistently achieving specification for the box and cam areas while reducing process variation.

A Step-Change in Productivity

Perhaps the most striking difference between ECM and CNC is throughput. CNC machining takes ~17 minutes per part to rough and finish the intercondylar area, whereas ECM machining takes only ~90 seconds per part when four implants are processed simultaneously in a multi-part fixture. This represents nearly an order-of-magnitude time savings. The impact on cost is equally dramatic: CNC operation cost: ~$11 per knee implant while ECM operation cost is ~$1.60 per implant. For high-volume production environments, these savings scale rapidly, delivering significant competitive advantage.

Precision Meets Productivity

ECM technology excels in targeted machining applications thanks to custom cathode design. The electrode (cathode) is engineered to match the implant geometry, ensuring material is removed only where required. In the case of the knee femoral intercondylar area, this means ECM can form the box and cam features without affecting adjacent bearing surfaces.

The result is not only improved efficiency but also guaranteed functionality of the implant. The smoother, more precise intercondylar geometry supports long-term performance in vivo, where durability and articulation are critical for patient outcomes. For materials such as CoCr, which are notoriously challenging to mill, ECM demonstrates exceptional efficiency — dissolving material as readily as stainless steel.

Enabling High-Volume Orthopedic Manufacturing

Knee implant manufacturers operate in a highly competitive and regulated market. Product differentiation often hinges on the following parameters:

Precision: Ensuring articulation and longevity of the implant.

Consistency: Meeting specifications across thousands of units.

Cost-effectiveness: Delivering competitive pricing without sacrificing quality.

Scalability: Maintaining throughput to meet global demand.

ECM supports all four by combining high productivity with superior machining quality. Its ability to rough and finish in one pass makes it ideal for high-volume orthopedic manufacturing.

Conclusion

The intercondylar region of a knee implant is one of the most demanding machining challenges in orthopedics. With the introduction of ECM for this application, manufacturers no longer need to compromise between precision, surface finish, and throughput.

Compared to CNC machining, ECM achieves 10× faster cycle times, more than 80 percent lower costs, and superior surface quality — all while eliminating heat and stress. For manufacturers, this translates into both competitive advantage and assurance of product performance. For patients, it supports implants that meet the highest standards of functionality and longevity.

As orthopedic implants evolve to meet rising expectations for mobility and quality of life, ECM machining of the intercondylar area represents a breakthrough in design and production strategy.

This article was written by Bruno Boutantin, Marketing and Business Development Director for Extrude Hone, Irwin, PA. For more information, visit here .