Tech Briefs: How'd you get started with this idea?

Professor Habib Rahman: It started from a project with our Connected System Institute, where we worked on a motor to make its digital twin to see if we could control the motors remotely. I have been working on rehab robotics for long time. My research is in rehab and assistive robotics. One group works with people who are stroke survivors, and another group works on wheelchair-bound users. During the COVID time, it was a struggle to help people rehabilitate. I had been working on rehab robotics — giving therapy with a robot. So, then we were thinking about how we could elaborate on our work with digital technology and our work with remotely operated robots. So, we used this idea to we see if we could do telehealth with a robot.

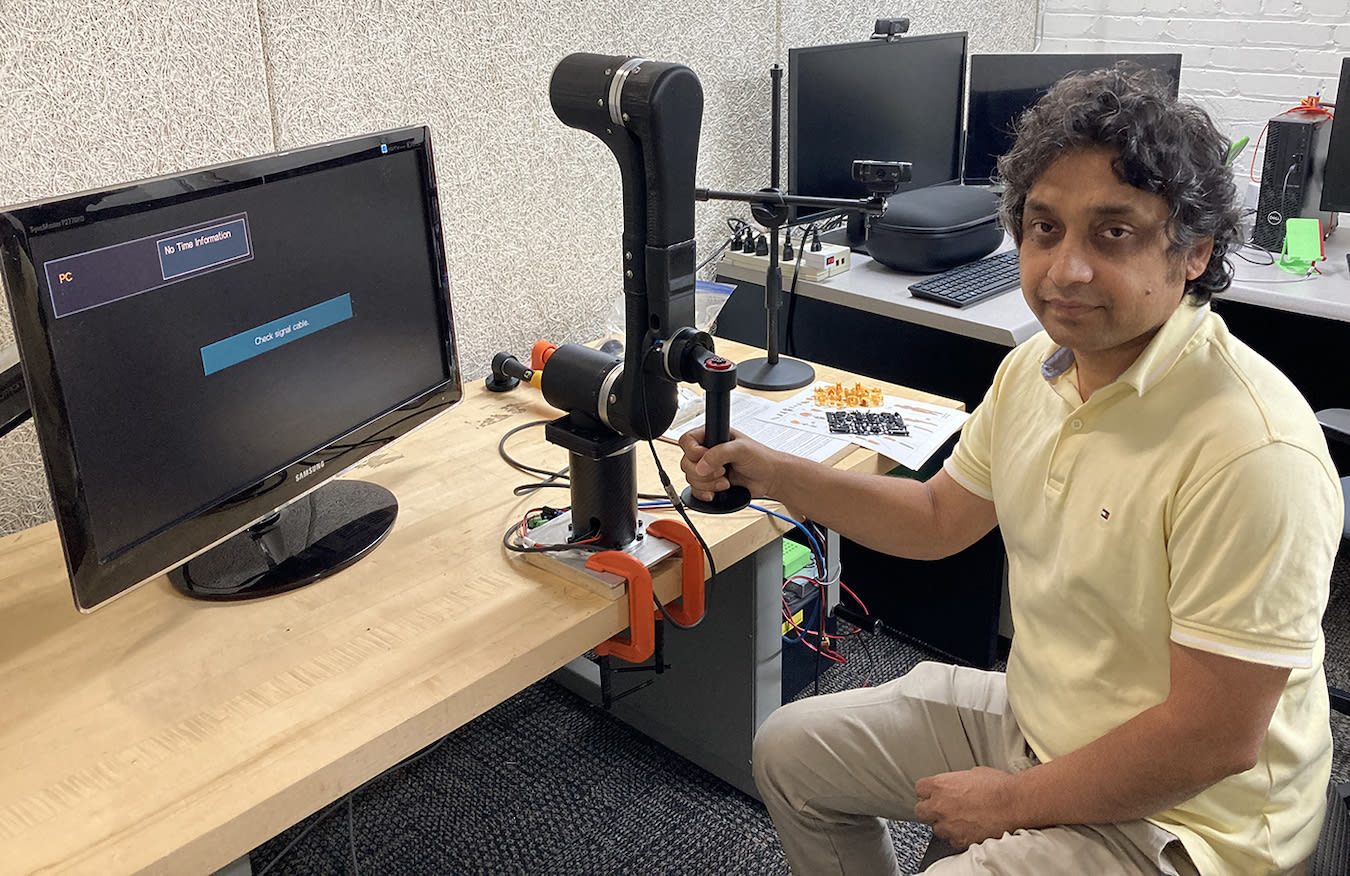

There were a lot of challenges at that time: smooth and safe operation of the robots and transmitting the data properly. This is not like a regular industrial robot. We need to see the robot in real time, see the patients, and get feedback. So, we started building our own.

Tech Briefs: So, in this robot arm, you have to vary the tension. How do you do that?

Rahman: The control algorithm can detect human intention of motions. We use two types of sensors: one is an electromyogram (EMG), another is a force sensor. We don't use EMG often — just to verify the system is working.

Tech Briefs: Could you tell me what an EMG does?

Rahman: An EMG signal comes from the muscle. So, if you try to move, we can know how it worked. We get a base electric signal and then we get one when the muscle is contracted.

Tech Briefs: Does the EMG signal give a pretty accurate measure of the muscle?

Rahman: Yes, if the person has a decent kind of arm movement. But, for stroke patients, it is difficult to get a good signal. However, if we amplify these signals for a healthy subject, it’s addressable. With a force sensor, if you try to move it means you are activating the muscles and we can get the signal, which is a measure of the quality of the physiology. Sometimes if I don't move my arm, for example, even if I am just holding a dumbbell, it's still using a muscle so we will get EMG signals. Any movement will have a muscle signal.

Tech Briefs: Doesn’t a myogram require inserting needles into the arm?

Rahman: There are two versions of myograms; using needles is one. But we use a surface EMG. It measures the potential difference between two electrodes that are held on the skin with adhesive. The control algorithm is such that if a person has good hand movement, the force sensor signal will dominate.

Tech Briefs: Where is the force sensor?

Rahman: It’s on the wrist handle, so the force sensors always detect your motions. Based on the subject’s impairment, the controller that can moderately adjust the assistance level or make it tough for the subject to move. If you make it tough, that means you are giving resistance and building muscles. There are a lot of therapies, for example, assisted therapy and resistive therapy. Based on the patient’s needs, we can program the controller to give assistance or resistance.

When you go to a physical therapist, they might ask you to push while they give resistance. Similarly, the robot will offer resistance — if you try to push it, it will make it a little hard. We program a goal and let the person get to the goal, but they will need to really push hard so that their muscle is working. Sometimes when we give them a target, if the person cannot make it, the robot will help them get there — this is called active-assisted therapy.

When someone suffers from a stroke, the connection of neural networks is kind of broken — the person forgets how to do small tasks, fine motor skills, so they need a lot of help. This requires a lot of repetitions, which the robot can give them — the device gently moves the participant’s limb without their own effort — this is called passive therapy. It stretches muscles without pain and reinforces correct movement patterns. Once the subject starts to gain real movement, we give them some functional tasks so that they can learn to coordinate.

Tech Briefs: Technically, how do you adjust the tension?

Rahman: We have a motor driver that adjusts the motor’s current based on the force sensor signal or EMG signal to change the motor’s actuations.

Tech Briefs: I read that there are two ways of using the robot — remotely or in person, say in a therapist’s office.

Rahman: It was always in person, but we are now exploring telehealth. We have different versions of the robot. One is really small and can go to a person’s home. Another version could go to a rehab center, where people can receive physiotherapy to set the therapy targets. The therapist can then get the data remotely, and when needed, adjust the therapeutic protocol, and even remotely control the robot.

Tech Briefs: Wouldn't this have to be guided by a therapist to decide how much is enough and how much is too much? I mean, you could harm somebody if you're not careful.

Rahman: Yes, we are working with stroke victims, getting data. However, once our AI is fully developed, less guidance will be needed, but therapists will always have to be in the loop. We will be working with many stroke victims to fully develop the AI to the point where we will need less supervision. However, we will still need therapists to program and supervise the robots. We are always enrolling subjects to work on the controller.

Tech Briefs: It seems to me it varies very much with the individual who's being treated. So, I'm not sure how without a therapist, even with the advanced AI, you could say for this individual this much force is needed.

Rahman: When you wire the robot, there is a law that can give you a pre-motion and will detect your pain period. Once there is muscle activation the pain will be increased, and the force sensor results will be increased. This is how we are working in our experimental phase.

Tech Briefs: Is this also measured by the EMG?

Rahman: Yes, both the EMG and the force sensor, but since we are developing the system, we are double checking with the therapist to decide whether this pain is OK. Then we enter that into the controller.

In the future there will be thousands of patients, every one of whom is different. We are using three things to measure the pain-free range of motion. The EMG sensor shows us the activity level, the force sensor shows us the resistance level, and we are using a camera, which can detect pain from facial expressions. This is not necessarily 100 percent correct because we are still in the development phase, but our long-term goal is to make a system that needs minimum supervision.

Tech Briefs: Are you creating a digital twin?

Rahman: Yes, the therapist doesn’t have the real robot, they have a replica of it. You can move the robot remotely and read the data that is being generated. You can see how much the joint angle has moved, how much force the robot has been subjected to.

The digital twin has two purposes. One is to control the robot remotely. Second, when the robot has moved, it sends out feedback so we can see how far it has moved. Once the subject has tried to move, we can see the magnitude and direction of the forces, the EMG readings, and so on. It’s a bidirectional communication.

Tech Briefs: So, you need transmitters as well as sensors?

Rahman: Yes, we use Microsoft Azure Cloud services. We send the signals to the Microsoft Azure cloud and then to the patient's home. If they are working without the therapist, the data will be stored in the cloud so the therapist can access it anytime.

Tech Briefs: I read that you use games.

Rahman: Research shows that robot therapy would give us improved performance by using games. There is scientific background on this, called motor learning principles. Based on that, we give the subject a task-specific guided therapy regimen. We give them the right challenge and collect explicit and implicit feedback about how far they are advancing.

So, a game is useful for that. We give the patient a task, say to go from one point to another. Once they go there, we make it little bit farther to increase their range of motion, to make it a little challenging for them. They know the course and they know exactly how long it takes. With games, it’s like the therapist is there. We use functional tasks in the games — washing, cleaning a table, taking a spoon from one place and putting it in another. The games are developed based on the motor learning principles, so since we use implicit and explicit feedback, they can monitor their improvement. Games are also engaging. It can feel a little boring doing repetitive tasks, but playing a game really engages a person. Improving your score can be motivating. Research our group has been doing shows that using games produces better outcomes.

Tech Briefs: What is the advantage of using this robot instead of just using a physical therapist?

Rahman: They complement each other. We have a constant shortage of therapists, and their numbers are decreasing. They can give the robot to the patient, and it can tirelessly work 24/7. It allows one therapist to see many patients during a day. Rather than having to sit with the patient while they do 10 repetitions, a robot can do that precisely.

It's a tool, like when my doctor gives me a blood pressure machine that they can monitor from home, so the doctor doesn’t need to come to check my pressure every day. In a similar way, this will help the therapist and the patient. Insurance covers only a limited number of physical therapy visits during the year. However, the robot will enable the patient to follow the therapist’s guidance for an unlimited time.

Tech Briefs: Looking ahead, who would pay for the machine? Would it be covered by insurance?

Rahman: I’m sure insurance will cover it because nowadays insurance covers continuous passive motion (CPM) machine rental agreements, if they are medically justified. But they just give you repetitions, nothing else. The robot makes it smart. So, since CPM machines are covered, we anticipate that the robot will be covered as well, since it is just like a CPM but with advanced functionality. A patient wouldn’t have to purchase the robot; it would just be a rental.

Tech Briefs: Where are you in terms of commercializing this?

Rahman: We are now running experiments with real stroke victims. I founded a startup last year and we are now working with a couple of other people who are helping us to commercialize the device. There are a few things that still need to be done. We could now sell it as just a robot for research purposes, but if we want to use it in a clinical home setting, we need to get FDA approval, which could take one to two years.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.