Many of today’s cutting-edge medical technologies utilize advanced sensors to help healthcare specialists provide unprecedented levels of care. Advanced systems and innovative methods allow for improved real-time data and more comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s treatment and overall health; this is true for all facets of medical care — preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, and overall assessment. With increased use of electronic monitoring technologies also comes the need to protect such sensors and other electronic components from anything that could compromise their performance. Parylene conformal coatings, for example, are often used to protect sensors from environments that can affect their performance over time. Whether they need to withstand potential exposure to simple humidity, pharmaceuticals, or even harsh cleaning and disinfection solutions, long-term sensor performance and reliability remains essential.

Parylene Conformal Coatings

For nearly five decades, Parylenes have provided protection for leading edge medical device technologies because they have dielectric and barrier properties; an ultrathin, pinhole-free nature, and outstanding thickness control due to the molecular-level polymerization. More recently, advanced adhesion technologies have provided further opportunities for the coatings’ use with historically challenging substrates.

Although some traditional liquid coatings can actually damage micro devices and electrical connections due to their sheer weight, curing forces created, or a combination of the two factors, Parylene coatings are applied in a vapor deposition polymerization (VDP) process that allows the coating to provide 100 percent coverage in a manner that minimizes stresses — both within the coating and to the underlying substrate. Components and devices to be coated are placed in a deposition chamber, and a granular raw material, known as dimer, is placed in the vaporizer at the opposite end of the system.

The double-molecule dimer is heated, causing it to sublimate directly to a vapor. The vapor then travels within the system to a higher temperature region for pyrolysis, which cleaves, or cracks, the dimer molecule into a monomeric vapor. The highly reactive monomer vapor then travels into the ambient temperature deposition chamber where it deposits onto all surfaces, combining end-to-end to form an ultrathin and uniform Parylene film. Throughout the deposition process, products remain at, or very near, room temperature, allowing any vacuum-stable substrate to be safely coated. Additionally, Parylenes contain no solvents, catalysts, or plasticizers, and there is no curing involved in the deposition process.

Parylene coatings are clear and free of fillers, stabilizers, solvents, catalysts, and plasticizers. They are extremely lightweight, offering excellent barrier properties without adding dimension or significant mass to delicate components. The coatings can be applied in thicknesses down to 500 Å, allowing for essential protection without adding undue bulk, stiffness, or other interference to sensor technology. As visually clear films, they are also well suited for optical sensors.

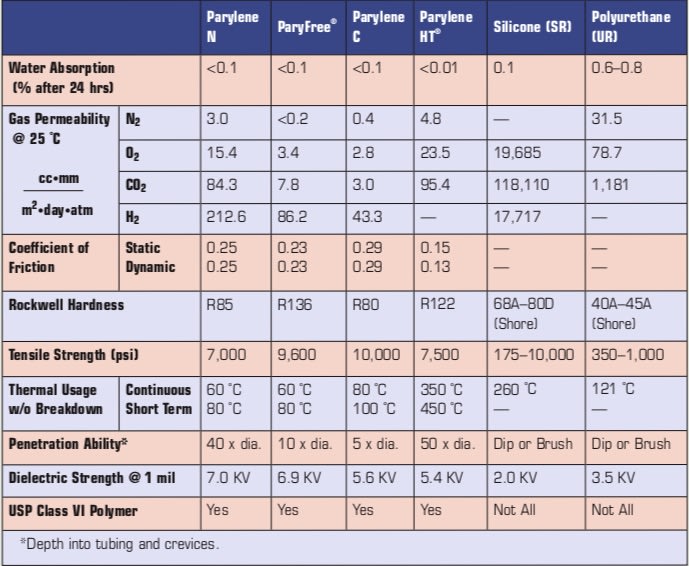

Three common variants of Parylene are used within the medical device industry — Parylenes C, N, and HT. Each of these variants conform to ISO 10993 biocompatibility requirements. ParyFree®, which was recently introduced as a commercially available variant, is also biocompatible and biostable; the coating offers manufacturers the same beneficial properties that they have come to expect from the Parylene family, but with improved barrier properties over traditional halogen-free variants. Key properties of each type are provided in the Table 1.

Applications: Preventive, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Healthcare

Preventive Care. Preventive care, as the first phase of medical care, continues to evolve into a partnership between a trained medical technologist and patient. Improvements in preventive care have been enabled by advanced sensor technologies that capture and share the patient’s key physiological measurements with medical personnel. Changes in measurements, then, are monitored and can signal the need for adjustments in medication, treatment, diet, or lifestyle.

Many of today’s wearables can simultaneously monitor and capture essential health information and even send alerts and reminders that increase a patient’s health awareness, such as when it might be a good time to take a walk or stretch. Today’s most common fitness trackers use sensors to capture pulse, respiration, and even blood oxygenation, but there are a handful of fascinating new wearable technologies that take additional vital measurements to supercharge preventive care. One such device incorporates electrocardiogram (ECG) technology that allows for monitoring heart health, including the ability to determine the presence of irregularities in a person’s heartbeat, also known as atrial fibrillation. Another breakthrough involves wearable blood pressure (BP) monitors that capture BP levels and changes as a function of daily activity, all useful information to assess overall health.

Wearables are subject to all of the environmental elements that may be encountered throughout a day, such as dust, dirt, moisture, and pollutants. Additional detrimental encounters may include perspiration, bacteria growth, and even sunscreen or food products. Protection of these sensors that capture key health-related data will enable devices to operate reliably and accurately, minimizing the overall cost of ownership by virtue of longer device life. Comparing a more budget-minded wearable to one incorporating a robust conformal protective scheme, such as the protection that Parylene coatings provide, could mean the difference between using a device for its reference value versus relying on technology to inform one’s health maintenance and improvement plans.

Diagnostic Evaluation. Diagnostic evaluation may be the most familiar segment of medical care. When a medical event has occurred, practitioners must evaluate where the medical issue lies and often need to continuously monitor patient vitals, including temperature, pulse rate, respiration, and blood pressure. Although many of these same types of measurements are common to those made in preventive care, diagnostic tools take on more critical tasks and are often higher-end systems designed to ensure quality results and reliable performance. They also often contain expanded capabilities utilizing sensors that can be organized into key categories, such as pressure, temperature, flow, and imaging.

Some preventive tracking devices monitor oxygen saturation, which is also a key diagnostic measurement and is a primary example of a sensor-driven technology. Like respiration and pulse, measuring oxygen content in the blood is critical in the real-time monitoring of a patient’s health. Pulse oximetry measures the oxygen saturation in a part of the blood called hemoglobin; this is accomplished with a unique sensor technology that utilizes light-emitting diodes of two specific wavelengths to measure absorbance through a part of the body. In most cases, a finger is used in a process where photodiode sensors measure the transmission of two different wavelengths of light transmitted through the tissue and blood of the finger and rely on specific calculations to determine the saturation level of oxygen bound to hemoglobin in the blood. Both the LEDs and the corresponding sensors have a limited life if left unprotected but can experience significant long-term reliability improvement when properly protected with a conformal coating such as Parylene.

A second example of diagnostic measurement is imaging technology. Today’s ultrasound devices use high-frequency soundwaves and their echoes to generate images with a transducer, or probe, that utilizes piezoelectric material. This piezoelectric material generates sound from electrical signals and captures the echo of that sound, converting it back into electrical signals to generate an image. Recently, a new kind of imaging sensor has begun to upset traditional piezoelectric ultrasound technologies. Wafer-generated capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers (CMUTs) are based on the same physics of capturing echoes of ultrasonic signals. Instead of using a transducer head to transmit to a signal-processing unit, however, CMUTs are manufactured with a different type of generator or sensor — one that is miniaturized and capable of being manufactured on the same semiconductor chip that processes all of the resulting data used to generate the final image.

Traditional ultrasound systems mount the signal-processing portion on a cart that is wheeled from location to location. The chip in a CMUT can be mounted on a cell phone as a temporary attachment, eliminating the need for a cart-mounted system that can cost up to $100,000. Although it is currently unable to generate the vivid images that standard ultrasound units can, CMUT technology is adequate for a variety of imaging requirements in a portable, low-cost unit. The integration of all elements on a single chip requires a protective scheme that can be applied in ultrathin, uniform fashion. Parylenes are uniquely suited to meet this challenge.

Therapeutic Technology. Therapeutic technology, the third phase of care, continues to become more sophisticated as complexity and miniaturization are applied to devices such as electrosurgical tools for laparoscopic surgeries, glucose monitors, insulin pumps, and many other devices. The same attributes of Parylene that have been utilized in other sensing technologies make them highly beneficial for providing conformal protection to therapeutic sensors in a stress-free, ultrathin coating.

Flow sensors are uniquely critical as they provide data that controls the administration of liquids and gases to sustain the patient. A variety of sensors can be used to detect gas flow on a ventilator, for example,— differential flow sensors, hot wire anemometers, and emerging technologies such as silicon micromachined thermal flow sensors and fiberoptic sensors. For each choice of flow sensor, maintaining accuracy and stability throughout the changes encountered in the sensor’s environment is critical. Protection is key because the constantly changing environment can include variation in gas composition, temperature, conditioning humidity, and additional moisture and other byproducts of the patient’s exhalation.

Also included in therapeutic care is the growing treatment of diabetes with devices that many hope will eliminate the need for frequent finger pricks and blood sugar measurements to determine appropriate insulin injection regimens. Both continuous glucose sensors and automated insulin pumps incorporate delicate sensing technologies that must operate consistently and reliably because an improper medication dosage can result in severe consequences for the patient.

Another therapeutic technology, laparoscopy, has been demonstrated as an effective, and often preferred, method of surgical care that minimizes surgical site infections and shortens recovery times, often eliminating hospital stays and lowering costs without sacrificing quality of care. The electrosurgical tools used during these procedures rely on materials that provide uncompromised electrical insulation, allowing for the precise delivery of energy to the targeted areas of tissue or blood vessels that are being cut, sectioned, or sealed as part of the medical procedure.

Additionally, the growing use of force sensors in some of these tools requires protections to maintain performance. For generations, highly experienced surgeons have relied on the feel of tissue-to-tool interaction forces to perform delicate surgical techniques. The direct feedback they rely on while handling medical instruments is largely lost when the surgery is performed in a minimally invasive fashion. Although minimally invasive surgery offers tremendous benefits, surgeons can experience one downside — reduced tactile sensation with respect to force, distance, or depth when sectioning and sealing tissue.

With the advent of robotic surgery, the feedback mechanism can be lost entirely, requiring a variety of sensors to measure force and displacement necessary for the successful completion of a surgical task. The use of feedback sensors is part of restoring the feedback mechanism. These sensors include load cells, strain gauges, and tactile force sensors that reside on the surgical tools themselves, allowing for a more reliable and repeatable outcome while imparting the least amount of induced trauma to tissue and organs.

Summary

Healthcare specialists and device manufacturers ongoing efforts to improve each stage of care are advanced with the use of sensor technologies. As these technologies become more complex and specialized, they often require protection, but such protection cannot interfere with the device’s sensitivity. Lightweight, ultrathin, biocompatible Parylene coatings provide the necessary protective and unobtrusive properties to achieve these objectives.

This article was written by Dick Molin, Medical Market Segment Manager, SCS Coatings, Indianapolis, IN. For more information, visit here .