Varied stakeholders in healthcare around the world increasingly share and recognize a requirement for standards-based interoperability.

The good news is that the necessary framework of interoperability standards is gathering form. Recent standards in areas such as blood-pressure monitoring, chronic-disease management, and three-dimensional (3D) modeling in medical applications exemplify the global e-health industry’s determination to improve multi-vendor interoperability, cost efficiency, and ease of use.

The E-Health Vision

A vision of e-health has taken shape around the world, and its proponents see in it the opportunity to bring about a host of key transformations—to better care for the world’s rapidly aging populations, to realize breakthrough cost efficiencies throughout the processes of healthcare delivery, to evolve from crisis-driven, responsive care to a more proactive posture of preventive care and wellness monitoring, and more.

In the developing e-health scenario, unprecedented volumes and types of more accurate data on patients and their environments—data that is both quantitative and qualitative, data that is sometimes processed and analyzed in real time—are securely and seamlessly exchanged through multi-layered networks of care. What capabilities could be unleashed?

- It could equip healthcare providers to more closely partner with their patients in preventive and post-operative care and in monitoring and management of chronic diseases.

- It could equip healthcare providers to more cost-efficiently serve the world’s remote, traditionally under-served communities.

- It could equip healthcare providers to more quickly and precisely identify and tamp down disease outbreaks and undertake preventive services across populations.

Standards-based interoperability of multi-vendor technologies is one of the critical underpinning elements of e-health. Diverse devices must “speak the same language” if data is to be exchanged seamlessly across the networks that interlink patients, healthcare providers, public-safety agencies, etc.

The importance of such interoperability is increasingly recognized among diverse players across the e-health landscape. For example, the FDA now includes interoperability-related standards in its guidance to the healthcare industry. A March 2013 report to the U.S. House of Representatives Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health from the West Health Institute concluded that, in the United States, standards-based interoperability among medical devices “could be a source of more than $30 billion a year in savings and improve patient care and safety.”

Managing Chronic Disease

Globally scoped standards help advance the multi-vendor interoperability on which e-health and all of its most promising benefits are predicated.

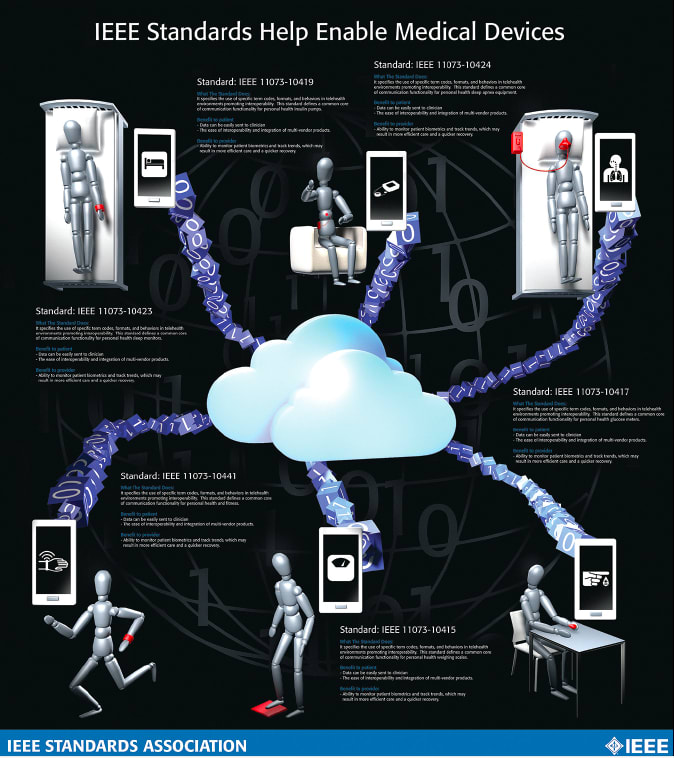

IEEE 11073 standards, for example, are designed to enable plug-and-play, seamless communications among various e-health devices and other healthcare systems and compute engines such as cell phones, personal computers, personal health appliances, and set-top boxes (See Figure 1).

Adoption of interoperability standards, such as those in the IEEE 11073 family, are intended ultimately to help individuals with chronic diseases like asthma, diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, high blood pressure, stroke, and atrial fibrillation lead more active, independent, and longer lives.

For example, one of the more recently approved standards in the family—IEEE 11073-10419-2015 “IEEE Standard for Health informatics - Personal health device communication - Device specialization - Insulin pump” ( http://standards.ieee.org/findstds/standard/11073-10419-2015.html )—defines a common core of communication functionality for personal telehealth insulin pump devices. Common terminologies, information models, application protocols, term codes, formats, and behaviors are proposed to improve interoperability among the devices used by diabetics.

Standards like IEEE 11073-10419 could potentially help eliminate the need for many of the customary, face-to-face appointments with care providers that patients must undertake today and replace them, instead, with more cost-efficient online interactions. Plus, with multi-vendor personal health devices able to feed information to healthcare providers via standards-based, interoperable communications, healthcare providers gain a more complete understanding of a patient’s ongoing condition—as opposed to having to base care decisions strictly on the information collected during isolated visits to doctor’s offices and other healthcare facilities.

Cuffless Blood-Pressure Monitoring

Similarly, innovation in wearable technology and “cuffless” devices for measuring arterial blood pressure stand to further enhance the quality of healthcare and lead to better health outcomes, and, again, the buildout of standards-based interoperability in this area is helping the world realize those benefits.

The cuffless capability is intended in part to enable unobtrusive, continuous, real-time, beat-to-beat measurement of blood pressure. It, furthermore, could be integrated in the design of watches, eyeglasses, mobile phones, clothing or electronic skin (“e-skin”) epidermal devices to support blood-pressure measurement anywhere and anytime. In such ways, the non-invasive, cuffless devices could be used to continuously monitor and analyze a patient even while he or she sleeps—for greatly enhanced remote, mobile monitoring of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular patients, for example.

While most of the world’s standards for evaluating blood-pressure meters were created for the traditional, common devices that use cuffs and usually capture “snapshot” measurements, recent standards development is helping pave the way for increased usage of cuffless devices. IEEE 1708-2014 “IEEE Standard for Wearable Cuffless Blood Pressure Measuring Devices” ( http://standards.ieee.org/findstds/standard/1708-2014.html ), for example, was designed specifically for this application and is relevant to wearable, cuffless devices, regardless of whether they are being used for measuring short-term, longterm, snapshot, continuous, or beat-to-beat blood pressure or blood-pressure variability. IEEE 1708 provides guidelines for manufacturers to qualify and validate their products, potential purchasers or users to evaluate and select prospective products and healthcare professionals to understand the manufacturing practices on the wearable devices.

3D Modeling

Medical 3D data acquisition devices for providing accurate spatial information for the human body are becoming increasingly available, and 3D modeling for diagnostics and therapeutic applications improves the clinical environment for better outcomes. Hardware capabilities and rendering algorithms have improved to the point that 3D visualizations can be rapidly obtained from acquired data.

And, yet, 3D reconstructions are not routinely used in the world’s hospitals, for multiple reasons. For one, physicians typically have been trained to gather information from two-dimensional image slices, not 3D. In turn, when displayed on traditional devices, 3D volumetric images are often of questionable value because of ambiguities in their interpretations. Furthermore, because of a lack of common methods among hospitals and research institutions for sharing such medical data, reusing or referring the data in collaborative healthcare research and related projects is complex.

A whole family of IEEE standards is growing to support increased reliance on 3D modeling and help spur on the advances in healthcare that it could convey. IEEE 3333.2.1-2015 “IEEE Rec - ommended Practice for Three-Dim - ensional (3D) Medical Modeling” ( http://standards.ieee.org/findstds/standard/3333.2.1-2015.html ), proposes volume rendering and surface rendering techniques for 3D reconstruction from 2D medical images, as well as a texturing method of 3D medical data for realistic visualization.

Other IEEE standards in this area are under development:

IEEE P3333.2.2 “IEEE Draft Standard for Three-Dimensional (3D) Medical Visualization” ( http://standards.ieee.org/develop/project/3333.2.2.html ) is being crafted to provide routine visualization techniques for 3D medical images.

IEEE P3333.2.3 “IEEE Draft Standard for Three-Dimensional (3D) Medical Data Management” ( http://standards.ieee.org/develop/project/3333.2.3.html ) is being developed to support secure sharing of 2D and 3D data among humancare managers and medical service providers for informing their decision-making processes.

IEEE P3333.2.4 “IEEE Draft Standard for Three-Dimensional (3D) Medical Simulation” ( http://standards.ieee.org/develop/project/3333.2.4.html ) is being written to address the simulation of the movement of joints and subsequent changes of skin, muscle, and neighboring structures.

Conclusion

With a wider array of more accurate patient data being efficiently, seamlessly and securely exchanged and analyzed end-to-end across existing and emerging medical systems and personal healthcare devices, the impact of standards-based e-health could be far-ranging.

Interoperability standardization on multiple fronts of e-health innovation is an important enabling element in the transformation that is playing itself out. Varied, complementary standards from the IEEE-SA and a host of other globally open standardization organizations will be needed in the decades ahead, in order to accelerate development of life-saving and life-enhancing capabilities and to ensure that the greatest potential benefits of e-health are realized around the world.

This article was written by Bill Ash, Strategic Technology Program Director, and Kathryn Bennett, Senior Program Manager, Standards Technical Program Operations, IEEE Standards Association, Piscataway, NJ. For more information, Click Here .