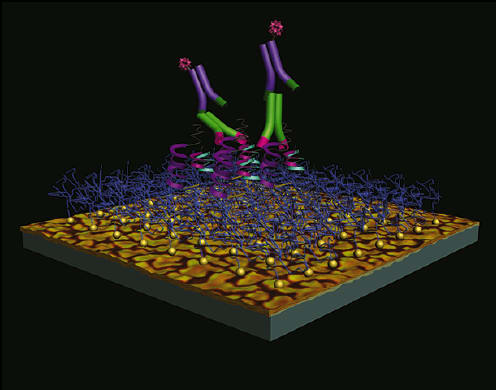

Researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, report that they have invented an inexpensive, portable, microchip-based test to diagnose type 1 diabetes that could speed up diagnosis, as well as enable studies of how the disease develops. The research was published online in Nature Medicine .

The test uses nanotechnology to detect type 1 diabetes outside hospital settings, and is expected to be used in a doctor’s office. According to Brian Feldman, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology and the Bechtel Endowed Faculty Scholar in Pediatric Translational Medicine: “We do hope that one day this technology will make it to point-of-care, i.e., in a physician’s office. It is likely that the first generation will be done in established Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) labs, we hope at the regional level and/or in house hospital lab settings in order to provide rapid turn around times.”

The handheld microchip can distinguish between the two main forms of diabetes mellitus, which are both characterized by high blood-sugar levels. However, the two types have different causes and require different treatments. But, making the distinction has required a slow, expensive test available only in sophisticated health-care settings. The researchers are seeking FDA approval of the device.

In the past, type 1 diabetes was diagnosed almost exclusively in children, and type 2 diabetes usually was found in middle-aged, overweight adults. But now, because of the childhood obesity epidemic, about a quarter of newly diagnosed children have type 2, and a growing number of newly diagnosed adults have type 1, the researchers say. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease causing patients’ bodies stop making insulin. The auto-antibodies are present in people with type 1, but not type 2 diabetes.

The old, slow test detected the auto-antibodies using radioactive materials, took several days, could only be performed by highly-trained lab staff and cost several hundred dollars per patient. In contrast, the microchip uses no radioactivity, produces results within an hour, and requires minimal training to use. Each chip is expected to cost about $20 to produce, can be used for up to 15 tests. The microchip also uses a much smaller volume of blood than the older test; instead of requiring a lab-based blood draw, it can be done with blood from a finger prick.