The clinical community stands at a pivotal moment. Historically, patient monitoring has relied on general laboratory testing providing sporadic clinical time points that often missed key disease dynamics. In contrast, on-body biosensors offer the potential for continuous, real-time tracking, enabling a shift in care from reactive to proactive, from generalized to personalized.

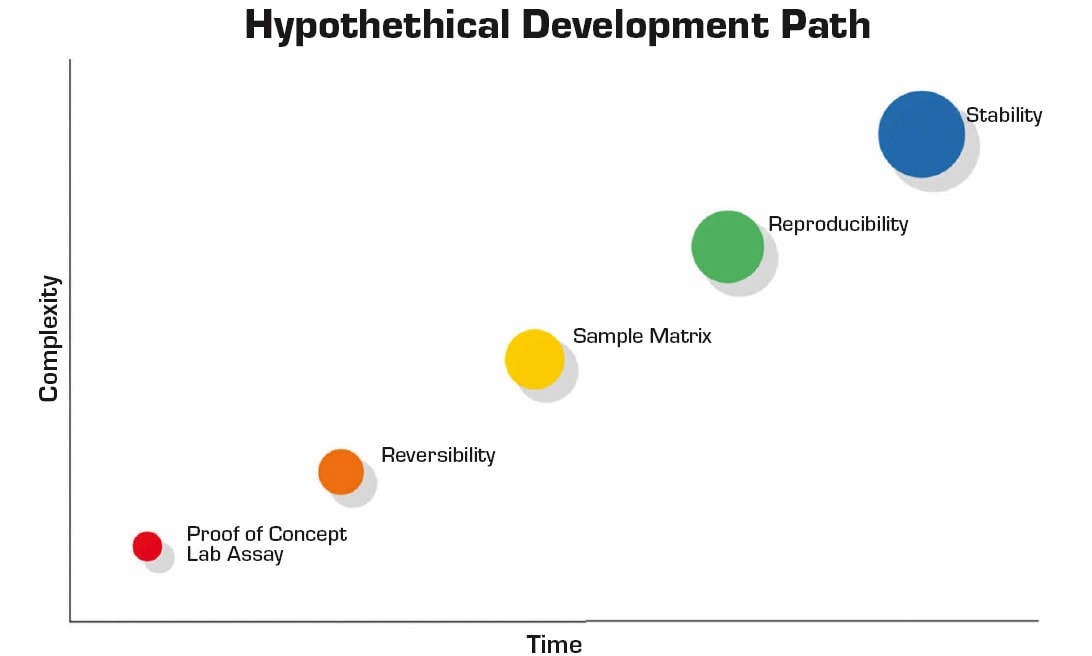

As excitement around on-body biosensors accelerates, so should scrutiny. The financial and human resources required to develop a viable wearable biosensor are immense. This expenditure will ultimately need to be recouped through commercial sales driven by patient benefits. Figure 1 depicts the transition for a hypothetical diagnostic from research concept to a commercial product. Each stage depicts a development challenge and could require an order of magnitude greater investment.

Ultimately, the path from concept to commercial product is fraught with technical and translational hurdles. Continuous monitoring presents additional requirements when transitioning a laboratory assay and is a strong focus of current research.1 Unlike discrete measurements, continuous measurement necessitates sensor/assay reversibility, and reversibility negates most analytical approaches.

Furthermore, the sample matrix, whether whole blood, interstitial fluid (ISF), or sweat, is exceedingly complex. Many laboratory-demonstration approaches never overcome the hurdle of a complex sample matrix. Additionally, reliable signal acquisition from the human body is a nontrivial feat. Human skin represents a dynamic interface that is affected by physical activity level, movement, temperature, and contaminants.

Reproducibility is the next major hurdle. It is often relegated to be the responsibility of manufacturing. However, for biosensors, this is not strictly the case. The dynamic nature of the skin interface, frequent use of biological components and inherent design limitations are issues that need to be resolved in research and development — even a robust manufacturing process will not address these underlying challenges. Addressing precision early in the development process has the added benefit of lowering testing volumes required to produce definitive results with sufficient statistical power.

Stability is required for both operating life and shelf life. Both elements are challenging especially with the inclusion of large biological molecules as part of the detection system. For operational life, the stability of the biological molecule is the most common failure point. While shelf-life verification dominates the critical path for most biosensor development projects, accelerated aging studies can compress timelines. However, this approach comes with significant risk especially as the temperature is increased.

Ultimately, biosensors must reliably interface with skin, access and accurately measure the target analyte in a complex matrix, perform reproducibly, and have sufficient stability to survive for the duration of the measurement.2 Due to the significant resources required to realize a wearable device, it is important that a stringent due diligence process be employed with respect to the utility of the envisioned sensor prior to progressing with an extensive development pathway.

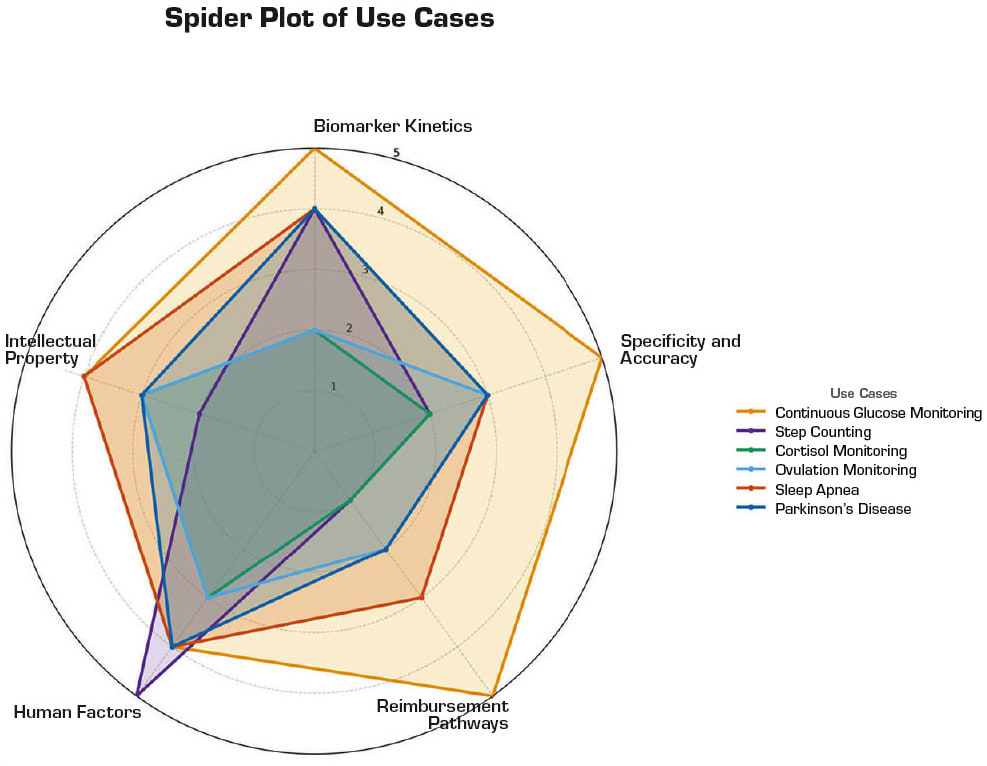

This article explores six clinical use cases for on-body biosensors and proposes a rubric for assessing their translational potential. The rubric considers clinical actionability, biomarker kinetics, reimbursement, and more.

Evaluating Success: A Rubric for On-Body Biosensor Companies

Given the crowded and rapidly evolving landscape, how can researchers and investors discern which biosensor applications and companies are likely to succeed? The following rubric, grounded in both technical and commercial realities, provides a structured approach to performing this due diligence exercise.

Clinically Actionable Information. The most successful biosensors do more than generate data. They provide information that directly informs clinical decisions. For example, the Dexcom G7’s real-time glucose alerts enable insulin adjustments.3 Without actionable outputs, devices risk being generators of only data and dismissed as mere novelty.

Biomarker Kinetics. The clinical relevance of a biomarker depends not just on what it represents but how quickly it changes. Continuous monitoring excels when biomarker fluctuations are rapid or clinically actionable in real time4 — such as glucose, where hypoglycemia can be life threatening. However, not all biomarkers benefit from such granularity. For example, thyroid hormone levels change slowly over weeks. In such cases, discrete lab tests remain sufficient. Similarly, the utility of measuring an analyte such as A1C that changes over the course of months would not justify the development of a continuous A1C monitoring biosensor. A1C could easily be recorded with sufficient granularity by means of an existing point-of-care or laboratory analyzer.

Specificity and Accuracy. Data fidelity suffers in the real world. Motion, hydration, temperature, and skin tone are hurdles to accurate data collection. Devices that correct for these (via multisensor integration or algorithmic compensation) produce more reliable outputs. The ability to distinguish a target biomarker from similar molecules is paramount. This is especially critical in hormonal and enzymatic sensing, where minor deviations can impact therapy.

Reimbursement Pathways. The presence of established CPT codes is a strong predictor of commercial viability. Devices that pair well with remote monitoring codes have a clear path to reimbursement and by providers.5

Human Factors and Usability. No matter how accurate, a device unused is a device failed. Wear time, calibration frequency, user comfort, and cosmetic appeal all influence patient adherence. Companies that prioritize human factors in parallel with sensor design emerge as leaders. The FreeStyle Libre 3 developed by Abbott is an excellent example of a continuous glucose monitoring system that minimizes patient burden and maximizes adherence.6

Intellectual Property. Strong patent portfolios with significant runway prior to expiration are more than legal shields — they indicate focused innovation and a sustainable commercialization advantage to bring protected technologies to market.

Representative Use Cases

With the rubric described above, this article explores six use cases and grades their translational potential in Figure 2.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has arguably set the standard for what is possible with on-body biosensors — with glucose levels being critical to assess for the diabetic patient that is using insulin to manage their disease. Glucose levels can change dramatically even in short spans of 5–10 minutes necessitating frequent measurements. CGM usage has been shown to reduce HbA1c, decrease hypoglycemic episodes, and improve quality of life for diabetes patients. The move toward closed-loop, automated insulin delivery systems further underscores the centrality of continuous, accurate glucose data.7

The earliest CGMs, introduced in the early 2000s, were hampered by short wear times, frequent calibration requirements, and poor accuracy.8 Current enzyme-based CGMs are highly selective for the target analyte with minimal interference from other endogenous species. After more than two decades of continual improvement, the human factors such as implanting the device to the on-body sensor, displaying glucose levels via the user interface, alarms, and insulin dosing are excellent. However, the IP landscape is now a minefield of incremental improvements on the underlying technology, which serves to slow new market entrants but not stop their access. The market success obtained by the CGM leaders (such as Dexcom G7 and the Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3) validates high rankings for this use case.

Step Counting. Step tracking, once a consumer novelty, has grown into a medically validated behavior change tool that has enabled improved weight management. The obesity epidemic and the plethora of comorbidities highlight the importance of this use case. While the general use of an accelerometer typically fails in terms of a biosensor as it lacks specificity and selectivity for clinical action, it is a viable tool for weight management.

Overall, the specificity and selectivity for tracking motion and resultant caloric expenditure is good. It is important to note that activity level is a dynamic measurement that is highly variable and requires frequent (continuous) measurement — this raw data stream is excessive and requires significant processing and interpretation. Critical IP covers the algorithms and data-processing methods. However, this type of IP provides limited protection. New entrants are going to be challenged by existing players in the space with significant market traction.

Cortisol Monitoring. Cortisol, the stress hormone, exhibits complex diurnal variation and is implicated in a range of conditions, from Cushing’s syndrome to depression and chronic fatigue. Most current methods to measure cortisol rely on salivary or serum sampling at isolated time points, and thus, miss dynamic patterns. There have been some efforts to develop wearable sensors for mental health and stress applications that target sweat or interstitial cortisol. However, these are currently with devices that are intended for maintaining and encouraging a healthy lifestyle instead of in the diagnosis, management, and treatment of a disease or condition. There are currently no FDA-cleared, on-body continuous cortisol biosensors with a medical claim.

While cortisol levels can be clinically useful for discrete monitoring of adrenal disorders, this use case scores poorly on the rubric described in this article. Kinetic profiles for cortisol typically change over hours and are confounded by several variables. Key hurdles for current sweat/ISF-based devices include specificity, the need for stable baselines and very low concentrations in noninvasive matrices. Without a defined clinical use-case and validated access method, devices remain either research-only or lifestyle enhancement tools for consumers. CPT codes to cover cortisol testing in clinical settings exist. However, there are no CPT codes to cover continuous cortisol monitoring apart from generic codes for remote patient monitoring. Recently, promising aptamer-based sensing methods have added to a largely sparse intellectual property landscape.

Ovulation Hormone Monitoring. Ovulation is driven by tightly regulated hormonal shifts, with luteinizing hormone (LH) surging about 24–36 hours before egg release and progesterone-driven basal body temperature (BBT) increases occurring after the event.9, 10 Most wearable devices today — such as Ava and Oura — integrate with natural cycles, track temperature, heart rate variability (HRV), and respiration trends to predict fertile windows. However, these are indirect markers and often confounded by illness, sleep disruption, or lifestyle factors. FDA-cleared products currently frame themselves as aids for ovulation prediction or contraception support, but their specificity remains modest compared to direct LH measurement.

On the rubric, ovulation monitoring scores moderately. Kinetics of LH are favorable for prediction, but noninvasive wearable access to LH or estradiol remains in early research, with sweat or saliva sensors showing proof of concept. Reimbursement is almost entirely consumer-driven, with limited HSA/FSA eligibility. Human factors such as comfort during sleep and adherence to nightly wear are manageable. The intellectual property landscape is open around multimodal sensing (temperature, HRV, activity) and for on-body hormone detection, which could meaningfully shift devices from retrospective confirmation toward prospective fertility planning.

Sleep Apnea Monitoring. Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repeated airway collapses during sleep, causing oxygen desaturation and autonomic arousals. Current home sleep apnea test (HSAT) wearables include WatchPAT, Sunrise, and Withings Sleep Rx. These devices use signals such as peripheral arterial tonometry, oxygen saturation, mandibular movement, or contactless under-mattress sensing to estimate apnea–hypopnea index (AHI). All are FDA-cleared and reimbursable under existing HSAT CPT codes, making them a rare example of a wearable class with established clinical adoption.

This use case scores highly on the rubric. Event kinetics are rapid and reliably captured by autonomic and oxygenation surrogates. Specificity challenges remain in patients with vascular disease, arrhythmias, or comorbid respiratory conditions, but multi-night monitoring improves reliability. Human factors are favorable: finger or chin patches are small and well tolerated, and contactless mats further enhance comfort. The intellectual property space is active in multimodal sensing (e.g., combining mandibular motion, acoustics, and oxygenation) and clinical workflow integration. The next frontier is extending beyond diagnosis into longitudinal management — using wearables not only to detect apnea but also to guide therapy titration and adherence monitoring.

Parkinson’s Disease Monitoring. Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition that causes unintended or uncontrollable movements, such as shaking, stiffness, and difficulty with balance and coordination. Given that there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, there is a significant focus on managing quality of life for patients with advanced stages of the disease. Motor symptom tracking for Parkinson’s disease has traditionally relied on infrequent, subjective assessments in clinics via MDS-UPDRS scores (International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society).11

With advancements in motion sensing and pattern recognition, in recent years, there have been several biosensors developed12 that enable continuous, objective monitoring of tremor, bradykinesia, and dyskinesia and facilitate remote patient monitoring. While motion data collection is reliable, the larger challenge is to help clinicians identify symptoms from motion data and align trajectories with medication timing and sleep. Ideally, a clinician could use personalized, symptom-tagged motion datasets to fine-tune dosage and account for a patient’s “on/off” periods.

This use case has clear potential in providing clinically actionable information. However, it scores moderately on the other elements of the rubric. Robust motion data trackers can capture motor symptoms with frequent changes. However, analyses of the collected data are affected by several inputs and confounding variables including the disease stage and the accuracy of medication log.

While there are some CPT codes for remote patient monitoring, the bulk of CPT codes applicable to Parkinson’s disease cover just its diagnosis. From a human factors’ perspective, on-body sensors for Parkinson’s disease monitoring are typically wrist or ankle-worn motion trackers that are easy to use but come with a daily wear burden for patients that already have challenges with mobility. Given that this space is trending toward software-defined biosensing with commodity hardware, the space has limited device-specific patents.

Conclusion

On-body biosensors have crossed the threshold from technological novelty to clinical tool driving medical decisions. The most successful devices share common traits: They provide clinically actionable information, reliably measure rapidly changing biomarkers, account for confounding variables, and utilize established reimbursement pathways. In domains like diabetes and cardiology, they are reshaping patient care. Yet, many biosensors remain stalled in translation, not because the technology is flawed, but because adoption depends on more than performance metrics.

To move from lab bench to patient worn device, developers must deliver not only reliable sensing but also reimbursement pathways, user-centric design, and systems integration. The rubric presented here helps distinguish high-potential solutions from over-engineered curiosities. It underscores that biosensor success is as much about workflow and clinical context as it is about sensitivity and specificity.

In the era of data-driven, decentralized care, biosensors will continue to define new standard of care but only if they lead to better decisions, not just more data. The future belongs to those who understand that utility, not novelty, is the final metric of value.

References

- Heikenfeld, J., Jajack, et al. (2019). Accessing analytes in biofluids for peripheral biochemical monitoring. Nature Biotechnology, 37 (4), 407–419.

- Gao, F., et al. (2023). Wearable and flexible electrochemical sensors for sweat analysis: a review. Microsystems & Nanoengineering, 9 (1), 1.

- Dexcom

- Bergkamp, M. H., et al. (2023). High-throughput single-molecule sensors: how can the signals Be analyzed in real time for achieving real-time continuous biosensing? ACS Sensors, 8 (6), 2271–2281.

- AMA, CPT Editorial Panel Summary of Panel Actions, September 2024.

- Abbott Freestyle Libre

- Lee, T. T., et al. (2023). Automated insulin delivery in women with pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 389 (17), 1566–1578.

- Hermanns, N., et al. (2022). Real-time continuous glucose monitoring can predict severe hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes: combined analysis of the HypoDE and DIAMOND trials. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 24 (9), 603–610.

- Ye, C., et al. (2024). A wearable aptamer nanobiosensor for non-invasive female hormone monitoring. Nature Nanotechnology, 19 (3), 330–337.

- Su, H. W., et al. (2017). Detection of ovulation: a review of currently available methods. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine, 2 (3), 238–246.

- International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

- Moreau, C., et al. (2023). Overview on wearable sensors for the management of Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Disease, 9 (1), 153.

This article was written by Mark Vreeke, Managing Member, and Atul Dhall, Engineering Consultant at Trans-Atlantic Science, Cypress, TX; and Aditi Dave, Independent Researcher. For more information, contact Vreeke at