For decades, robotic-assisted surgery has offered physicians enhanced precision and minimally invasive approaches, but the systems in operating rooms today still require the surgeon to control every motion. While robots can augment a surgeon’s dexterity, they have not yet operated on their own.

That milestone is beginning to change. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University recently demonstrated the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR), completing eight consecutive gallbladder removal procedures on ex vivo tissue without human intervention. Unlike prior robotic systems trained only in structured environments, STAR learned from surgical videos, enabling it to adapt to variability, self-correct in real time, and even communicate its intent to the surgeon.

The achievement has implications beyond the operating room. For engineers and device developers, STAR highlights the convergence of machine learning, computer vision, real-time sensing, and advanced control systems — technologies that must function seamlessly while maintaining patient safety. It also underscores a critical industry challenge: how to deliver safer, more efficient care in the face of rising surgical demand and a shortage of trained physicians.

Medical Design Briefs spoke with Axel Krieger, PhD, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins and senior author of the study, about the system’s architecture, safeguards, and future applications.

MDB: Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your role in this research?

Axel Krieger: I’m an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins and served as a senior author on this work. The bulk of the research was done in my lab with an outstanding group of postdocs and students. We also had important contributions from collaborators across multiple disciplines. This was truly a team effort — it takes both engineering innovation and clinical expertise to make an advance like this possible.

MDB: How did training the robot on surgical videos, instead of highly structured environments, change its capabilities?

Krieger: Robotic-assisted surgery today requires the surgeon to manually guide every step from a console. Our approach shifts the paradigm. Instead of the surgeon executing each movement, the robot can take on subtasks autonomously, while the surgeon supervises. We used imitation learning, training the system by having it watch videos of expert surgeons. This allowed STAR to absorb not just the “ideal” steps but also the subtle adaptations surgeons make in real-world conditions. Prior automation efforts were limited to very small tasks, such as picking up a needle or placing a single suture. By training on surgical videos, we expanded autonomy to entire steps of a procedure. It’s a fundamental difference in scope and adaptability.

MDB: What safeguards or feedback mechanisms are in place to ensure safety when dealing with variability or complications?

Krieger: Safeguards were built into every level of the system. In our gallbladder study, STAR demonstrated the ability to recognize small misplacements — for example, a clip that didn’t perfectly align with the artery — and then correct itself without human help. That capability was crucial, and it’s something that even experienced surgeons must do routinely. We achieved this with a hierarchical architecture. At the top level, a video analysis network reviews the surgical field, compares the current frame with past frames, and identifies what step of the procedure is under way. It flags whether things are progressing normally or if a correction is needed. The system then generates a natural-language explanation of what it sees — for instance, “placing the first clip on the artery.” At the lower level, a controller executes the maneuver. This controller was trained on datasets of expert surgeons performing the tasks, as well as on examples of corrections. By including corrective actions in training, we taught the robot not only what to do, but how to adjust when the initial attempt isn’t perfect. The result was eight consecutive clipping-and-cutting steps completed without intervention.

MDB: The robot responded to voice commands and learned from them. How does this interactivity enhance human-robot collaboration?

Krieger: Imagine a robot that works silently and independently — it would be very difficult for the surgeon to know what’s about to happen. Instead, STAR communicates. It tells the surgeon its planned action, such as “I will now place the clip on the artery.” The surgeon can then confirm or redirect, saying, for example, “No, clip the duct first.” During training, this type of interaction was critical. The robot would announce its intent, and the surgeon could override or correct it. Those corrections became part of the learning process, helping STAR refine its behavior. By the time we reached testing, the system no longer needed corrections; it performed the steps correctly on its own. This interactivity lays the groundwork for true collaboration. The surgeon remains in control, but the robot provides transparency and a clear communication channel — essential in any high-stakes environment like the OR.

MDB: What regulatory, ethical, or training considerations need to be addressed before autonomous systems are used in live surgeries?

Krieger: Thus far, we’ve demonstrated success in ex vivo studies — procedures performed on tissue from a butcher shop. The next step is live animal studies, which are the standard pathway to proving safety and effectiveness before human trials. If those are successful, we can pursue regulatory approval for first-in-human studies. It’s important to stress that our vision isn’t a future where robots replace surgeons. A better analogy is autonomous driving. We didn’t leap from fully manual cars to vehicles with no steering wheels. Instead, autonomy came gradually, with features like adaptive cruise control or lane keeping. Surgical autonomy will evolve similarly. STAR may handle certain repetitive or technically demanding subtasks — suturing, clipping, or cutting — while the surgeon supervises and makes higher-level decisions.

This evolution is timely. The surgical workforce faces mounting pressure: our society is aging, the number of surgeries is climbing, and the supply of trained surgeons isn’t keeping up. Autonomy can help relieve that pressure by making procedures more efficient and supporting surgeons where the workload is greatest.

MDB: Why was gallbladder surgery chosen as the first target, and what procedures might be next?

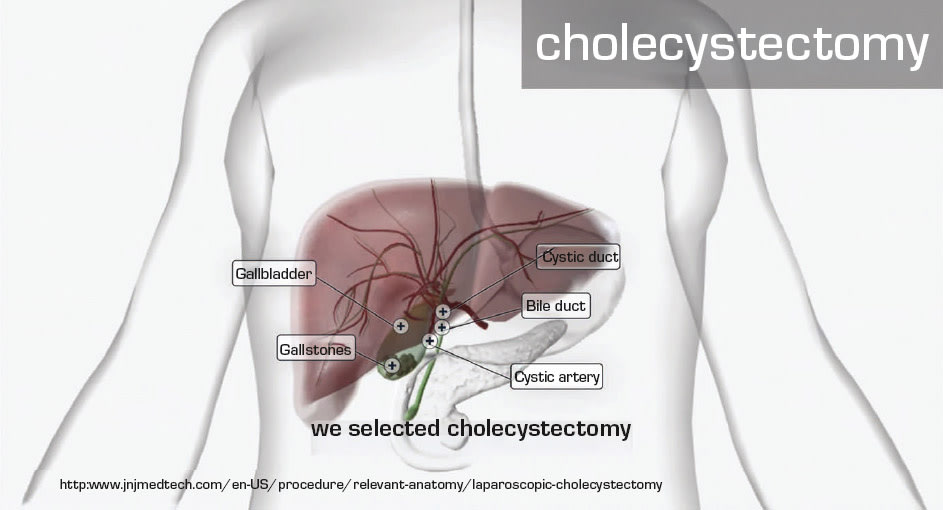

Krieger: Cholecystectomy, or gallbladder removal, was the first minimally invasive surgery. It transformed practice from large open incisions to laparoscopic approaches with small ports and cameras. That history made it a symbolic and practical choice for demonstrating autonomy.

It’s also a high-volume procedure, performed hundreds of thousands of times each year. The complexity can range from simple cases with minimal inflammation to challenging ones with severe adhesions and anatomical variations. That gradient made it ideal for testing STAR’s adaptability. Looking ahead, we see strong potential in tumor resection surgeries. These are particularly demanding because surgeons must integrate live camera images with preoperative data such as CT or MRI scans. They need to mentally map the tumor’s location relative to critical anatomy. If we can incorporate that preoperative information into STAR’s framework, the robot could assist in navigating these complex spatial challenges — something that could greatly aid surgeons.

MDB: From an engineering perspective, what are the biggest design challenges that remain?

Krieger: Reliability is at the top of the list. An autonomous surgical system must work consistently across thousands of cases and diverse patient anatomies. That requires large, diverse datasets and extensive validation. We also need seamless integration of multiple technologies. The system must combine high-resolution imaging, real-time sensing, and AI decision-making with extremely low latency. Any delay in a surgical environment is unacceptable. Human factors are equally critical. Surgeons must be able to interact intuitively with the robot, understand its decision-making, and step in at any moment. Designing user interfaces that are clear, transparent, and aligned with surgical workflows will be just as important as improving the algorithms.

Finally, regulatory compliance presents its own engineering challenges. Demonstrating safety requires not only strong performance but also traceability, documentation, and rigorous testing protocols. Engineers will play a central role in building systems that meet these standards.

Looking Ahead

The success of STAR marks a turning point in surgical robotics. Just as laparoscopic cholecystectomy redefined surgery three decades ago, autonomous systems may soon reshape how operations are performed.

For engineers, it is important to understand that the future of surgery will depend on advanced algorithms, robust control systems, and human-centered design. STAR’s achievement is not the end point but the beginning of a new phase — one where robots don’t just assist surgeons but also think, adapt, and learn alongside them.

For more information, contact Axel Krieger at