The use of platinum-iridium (PtIr) alloys for pins and electrodes in medical devices is growing substantially in applications such as cardio and neuromodulation devices. In this article, pens are defined as those used in feedthroughs for ceramic implants, generally straight wire with specific cutoff features on the ends, and electrodes are defined as those providing direct electrostimulation to tissues, which are essentially wires that have additional features machined into them. The benefits and features discussed herein, using additive manufacturing (AM), also apply to other types of PtIr components, where the end pieces can be fabricated from different preforms besides wires. The ongoing miniaturization of implantable and insertable devices is magnifying the need for controlling the bulk metal material consistency. Cost is always an important issue as well.

Recent developments in creating PtIr powders by atomization have opened up possibilities to produce PtIr components using AM techniques. The overall production steps with AM are generally shorter compared to conventional techniques, with a specifically smaller equipment effort and material-efficient production cycles.

Analogous benefits in using AM for PtIr alloys apply to gold-based alloys. This article focuses on PtIr applications.

Powder Technology

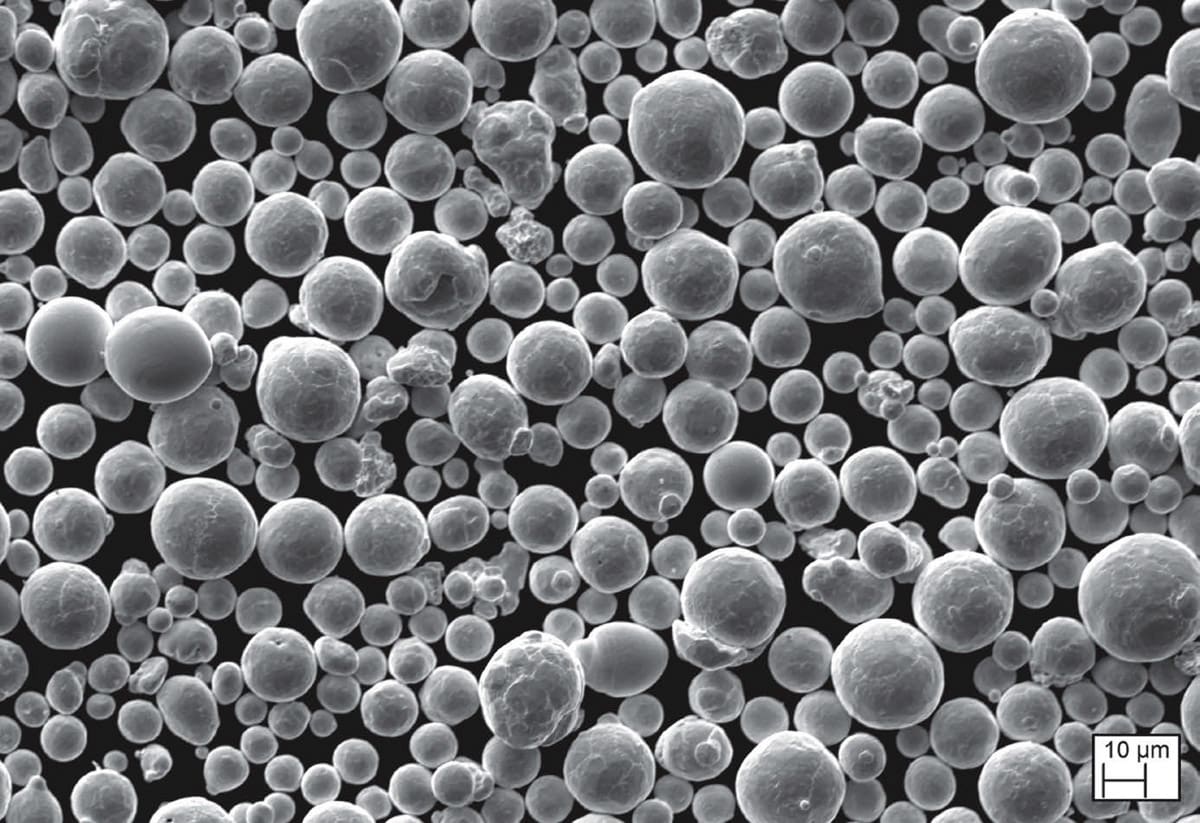

Two keys to success with any AM process include consistent particle size distribution and uniform spherical particle shape. Where the 3D structure is built by fusing the powder layer by layer, aka, 3D printing, a particle size distribution of between 9 and 52 μm was found to be optimal. Too narrow a range could impede flow with the potential for the particles to clump together.

Additional uses for the powder include metal injection molding, brazing powders, and other applications. Size distribution for these processes typically require a maximum particle size of 25 μm. A particle size distribution of 5–25 μm can be maintained for such applications. Any particles that are outside the specified size range could easily be transferred back to the furnace, where reatomization could be done in subsequent production. No refining is required as the alloy does not change during atomization. One key benefit of powder-based technologies is the direct reuse of excess powder without new energy-intensive melting processes.

Background

PtIr alloys are used in medical applications for the following reasons: biocompatibility, electrical conductivity, high density, ductility, chemical inertness, mechanical robustness, resistance to corrosion, and radiopacity. The mechanical and thermal properties, as well as corrosion resistance, increase with increased Ir content. While the PtIr alloy composition can be customized to a particular need, in medical applications, it is easiest to use those that meet approved ASTM specifications, which include platinum/iridium ratios of 95/5, 90/10, and 80/20.

Grade 90/10 is the most widely used, due to its balance of cost, mechanical properties, and processability. Grade 80/20 is used where the mechanical strength and/or corrosion resistance are the most critical. For the small pins and electrodes, most of the cost is not the raw material but the combination of processing and fabrication. Grade 80/20 has the highest processing costs and is the most difficult to work with, from alloy casting to forming to final part fabrication.

The following sections provide a comparison between conventional and AM processing. For both process scenarios, after alloy melting, the material is typically made into a preform, such as a bar, sheet, tube, wire, or similar shape of specified dimensions, which is then to be fabricated into the final configuration.

Conventional Process

Platinum and iridium are melted together in a high-temperature vacuum furnace at the specified weight ratio to create a uniform mixture, where the molten material is cast into ingots and then cooled for further processing. The casting process must be tightly controlled to develop a consistent grain microstructure and to prevent or minimize formation of gas pockets. The microstructure of the material, i.e., the arrangement of atoms, the grain size and/ or the presence and the number of defects, such as porosity, will affect results of the fabrication processes. The bulk material key features of microstructure and porosity will affect the resulting mechanical properties of a drawn wire, as well as its surface finish.

Shrinkage porosity and surface inconsistencies are known to be highly likely defects when casting Pt alloys. While 80/20 is the most difficult to cast of the three approved PtIr alloys, including being the most susceptible to gas pocket formation, 90/10 and 95/5 have the same concerns. To ensure consistent product quality, manufacturers use several complex postprocessing technologies including, for example, hot forging.

After casting, the cooled PtIr ingot can be subjected to hot working by rolling or forging, which refines the grain structure and improves the mechanical properties. The alloy is further processed through cold working techniques that can include drawing or rolling to achieve the desired wire form. Cold working, i.e., drawing or rolling without heat treatment, changes the crystalline structure which increases the strength and hardness of the alloy. Annealing, i.e., heating the material above its recrystallization temperature and maintaining temperature for an appropriate amount of time and then cooling, can be used, if or when needed, to relieve internal stress and recover ductility to make the wire easier to draw into finer diameters.

The challenges of conventional manufacturing of PtIr semifinished products by vacuum casting requires extensive and tight process control throughout the entire process chain to produce a homogeneous grain structure, 100 percent density, and uniform properties. Finally, the efficiency of fabrication using CNC milling, turning, laser cutting, etc., as final steps in component production is dependent on the quality of the workpiece, whatever preform configuration is used.

Additive Manufacturing Process

To produce the PtIr powder, no ingot is necessary for atomization. Platinum and iridium are placed into the crucible at the specified ratio of the materials and the molten material is fed into a gas atomizer to produce PtIr powder. Upon cooling, the powder is sieved to separate the specified particle diameter range. Any particles that fall outside the specified range can be easily returned to the powder production process and serve as input material for the next batch of atomizing, for high efficiency of metal use. This is highly cost-effective if the atomizing is done at the same facility as the AM process. 1

The chosen AM process was selective laser melting (SLM) because it produces fine, uniform, and denser microstructures compared to selective laser sintering (SLS). SLM has faster cooling rates, which helps to produce the superior microstructure, especially important for applications that have miniaturized features or demanding mechanical performance.

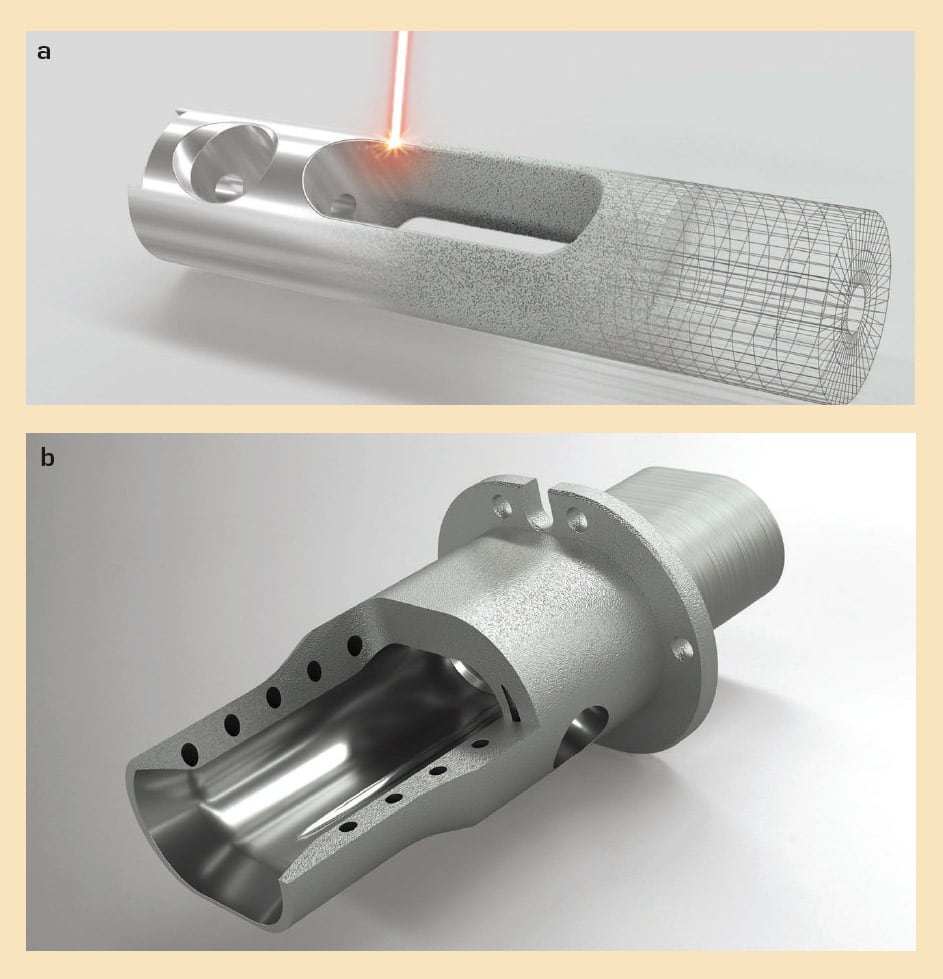

PtIr alloys manufactured by SLM exhibit, moreover, a finer grain structure than in conventional production. The extreme fine grain structure of SLM parts is achieved by rapid cooling after laser melting and not by forming and heat treatment processes, as with conventional manufacturing. This means it will produce both higher yield and ultimate strength. Wall thickness can be printed to 0.012 in./0.3 mm and holes down to 0.02 in./0.5 mm diameter. Ongoing developments in the SLM process should be able to reduce the as-printed feature dimensions in the near future.

The AM equipment used has a high level of built-in process control and monitoring capabilities. The powder bed is automatically monitored by a high-resolution camera, which can also image the continuous state or form of the component, layer by layer. Other sensors produce a real-time display of conditions, with alarms preset if there is, for example, a layer of powder that is not consistent. Multiple lasers can improve features and throughput in some instances, if needed. Through the described process control and postprocessing, a dense powder metallurgical component can be ensured. The physical properties using AM are comparable or exceed the conventionally produced parts.

Using AM for 80/20 magnifies the benefits of the overall process efficiency improvements. The difficulties in processing 80/20 using the conventional manner leads to relatively low efficiency. This means that the final cost and reliability issues are increased, accordingly. Because 80/20 is more difficult to produce than 90/10 in conventional processing, the process costs are multiplied well beyond the raw material cost alone. AM makes 80/20 a more viable option, especially for small batch sizes, as it improves manufacturing efficiency and consistency and reduces costs.

Another benefit of SLM is that the simplified processes and the possibility of near-net-shape designs can be very beneficial for the rapid production of prototypes. There is further potential in multi-metal production, in which PtIr is printed over a nonprecious metal substrate to integrate parts or reduce the use of precious metals. The feasibility of each application would have to be analyzed individually.

Cost Comparisons

Reducing the number of processing steps to get to the desired dimension of CNC prematerial reduces costs when using AM.

When machining an as-printed component to achieve tighter tolerances or modified features, the near-net shape reduces costs by reducing the overall milling time.

Machining the final component from a PtIr bar or wire can generate from 50 to 80 percent scrap depending on the amount of material removal. AM can significantly reduce scrap rate.

In a study of a 4.4-gram electrode, the CO2 footprint made of PtIr 80/20 can be reduced by 31 percent through additive manufacturing (2.2 vs. 3.2 kg CO2 per part) due to lower energy. This is driven mostly by the reduced scrap waste and overall material usage per part. The CO2 reduction translates to final component cost reduction.

Multiple near-net shape parts could be printed onto one workpiece for more efficient machining setups.

Regarding only the costs, there is a breakeven point depending on the batch size and the complexity of the parts. Conventional production is often more cost-effective for large quantities and simpler geometries, due to economies of scale. Additive manufacturing has advantages for prototypes, small batches, and complex geometries.

In Summary, AM Benefits

Simplified processes → reduced variability → improved bulk material consistency → reduces costs → improves final part integrity.

Fast prototypes, minimal setups.

High flexibility for complex parts.

Highly automated, 24-hour, lights-out manufacturing.

In-process quality control; multiple monitoring sensors and high-resolution camera(s).

Numerically controlled.

Low carbon footprint — AM emits ≥30 percent less CO2 than conventional processes.

Near-net shape.

Post-print machining for tolerance and feature optimization.

80/20 becomes a more viable option material.

PtIr jewelry, as well as 18 ct gold jewelry, requires perfectly dense material of over 99.99 percent. Porosity is not acceptable to achieve the demanding, highly polished, defect-free material, where any minuscule imperfection in the bulk printed material would stand out after the as-printed surfaces are milled/polished. Thousands of such SLM-produced components have been made in lights-out, continuous production, which confirms the consistency of the AM manufacturing process using Pt- and Au-based alloys. The same high level of porosity-free bulk material in medical devices leads to consistent material strength, surface finish, and final performance reliability. Note that the hollowed interior features produced by SLM shown in the example photos can reduce overall weight and cost of a PtIr component.

Reference

- Shaun Cooke, et al., “Metal additive manufacturing: Technology, metallurgy and modelling,” Journal of Manufacturing Processes, Vol. 57, September 2020, pp. 978–1003.

This article was written by Andy Michalow, Representative for C.Hafner North America, a fully integrated manufacturer of precious metal refining, alloys, preforms, additive manufacturing, CNC machining and micro-machining, and surface treatments to produce finished medical components and/or assemblies, established in 1850. For more information, e-mail Andy Michalow at