If scientists are ever going to deliver on the promise of implantable artificial organs or clothing that dries itself, they’ll first need to solve the problem of inflexible batteries that run out of juice too quickly. They’re getting closer, and researchers report that they’ve developed a new material by weaving two polymers together in a way that vastly increases charge storage capacity. The researchers presented their work at the 255th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

“We had been developing polymer networks for a different application involving actuation and tactile sensing,” Tiesheng Wang says. “After the project, we realized that the stretchable, bendable material we’d made could potentially be used for energy storage.”

Batteries, specifically lithium-ion batteries, dominate the energy storage landscape. However, the chemical reactions underlying the charging and discharging process in batteries are slow, limiting how much power they can deliver. Plus, batteries tend to degrade over time, requiring replacement. An alternate energy storage device, the supercapacitor, charges rapidly and generates serious power, which could potentially allow electric cars to accelerate more quickly, among other applications. Plus, supercapacitors store energy electrostatically, not chemically, which makes them more stable and long-lasting than many batteries. But today’s commercially available supercapacitors require binders and have low energy density, limiting their application in emerging go-anywhere electronics.

Wang, a graduate student in the lab of Stoyan Smoukov, PhD, at the University of Cambridge (UK) suspected that a flexible conducting polymer-based material from another project they were working on could be a better alternative. Conducting polymers, such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythio-phene) (PEDOT), are candidate supercapacitors that have advantages over traditional carbon-based supercapacitors as charge storage materials. Conducting polymers are pseudoca-pacitive, meaning they allow reversible electrochemical reactions, and they also are chemically stable and inexpensive.

However, ions can only penetrate the polymers a couple of nanometers deep, leaving much of the material as dead weight. Scientists working to improve ion mobility had previously developed nanostructures that deposit thin layers of conducting polymers on top of support materials, which improves supercapacitor performance by making more of the polymer accessible to the ions. The drawback, according to Wang, is that these nanostructures can be fragile, difficult to make reproducibly when scaled-up, and poor in electrochemical stability, limiting their applicability.

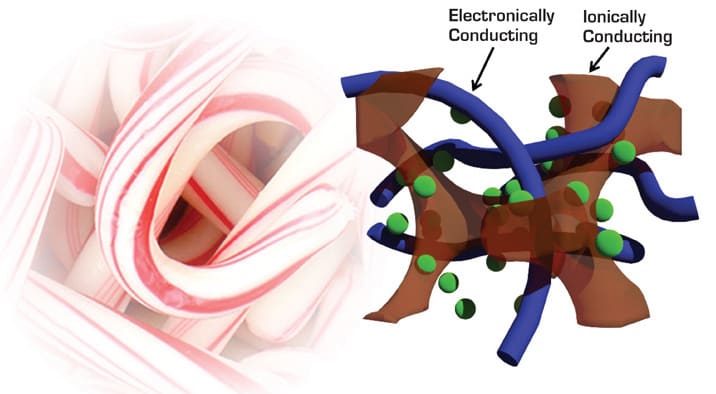

So, Smoukov and Wang developed a more robust material by weaving together a conducting polymer with an ion-storage polymer. The two polymers were stitched together to form a candy cane–like geometry, with one polymer playing the role of the white stripe and the other, red. While PEDOT conducts electricity, the other polymer, poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), can store ions. The interwoven geometry is instrumental to the energy storage benefits, Wang says, because it allows the ions to access more of the material overall, approaching the “theoretical limit.”

When tested, the candy cane supercapacitor demonstrated improvements over PEDOT alone with regard to flexibility and cycling stability. The candy cane supercapacitor also had nearly double the specific capacitance compared with conventional PEDOT-based supercapacitors.

Still, there’s room for improvement, Smoukov says. “In future experiments, we will be substituting polyaniline for PEDOT to increase the capacitance,” he says. “Polyaniline, because it can store more charge per unit of mass, could potentially store three times as much electricity as PEDOT for a given weight.” That means lighter batteries with the same energy storage can be charged faster, which is an important consideration in the development of novel wearables, robots, and other devices.

Smoukov acknowledges funding from the European Research Council. Wang thanks the China Scholarship Council for funding and the UK Centre for Doctoral Training in Sensor Technologies and Applications of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council for support.

For more Information, visit here .